I am sharing today Franz Liszt’s “La Campanella” (Italian “the little bell”), which is the third of the six etudes in Liszt’s work Grandes etudes de Paganini, where the composer reworked Paganini’s Violin Concerto No.2 in B Minor for piano. The composition below is played by American pianist André Watts (1946-2023), and I somehow prefer it over other hastier renditions. This piece is considered challenging not least because it requires a very light touch (to sustain the bell-like quality of the notes) and excellent dexterity to take on its fast, large leaps, trills and tricky ornaments. The piece’s gentle start soon unveils surprising buoyancy and vibrancy, a flowing (“torrent of water”) progression, before culminating in a passionate, even violent, coda, making it a very memorable piece. Overall, a virtuosic gem.

Review: Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker

Cassandra at the Wedding [1962] – ★★★★

Cassandra Edwards is a graduate student who is supposed to be finishing her thesis and enjoying her student life. Instead, she is an emotional and mental mess, a state that no one sees and only her twin sister Judith guesses. When the date of Judith’s wedding approaches near, Cassandra drops everything and goes back home to attend the event, but the homecoming is not altogether joyful as Cassandra (packed with her bitter-sweet memories, unrealised hopes, deep attachments and her neurotic fears of betrayal) starts to spiral out of control. Judith’s impending wedding may be a catalyst for Cassandra’s final unravelling. Baker’s novella is direct and unrelenting; a book that examines closely one unbreakable bond and one fractured mind, all from the point of view of one subversive, unforgettable narrator.

Continue reading “Review: Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker”A Boyar Wedding Feast

A Boyar Wedding Feast is a painting by Konstantin Makovsky that showcases a very important social event in old Russia, a wedding feast that united two prominent Boyar families. In a richly decorated room, the lavishly attired guests (with gold trimmings in their clothing) are caught in the key moment of the event – the groom is about to kiss the bride during a toast, as a dish of fried swan, in turn the symbol of fertility, is presented by one of the servants. As everyone cheers the couple on, the groom is trying to turn the bride to his side, while the matchmaker is seen behind the bride, prompting her to action. However, the bride herself is looking down shyly, almost with a sad or resigned expression. The unspoken feeling is that she should be happy to get married and it is unlikely that her own wishes in the matter were ever considered.

Continue reading “A Boyar Wedding Feast”Orpheus and Eurydice

I hope all my followers and readers had a very Merry Christmas, and I would like to wish all a very Happy New Year. We are now in January, named after Roman God Janus, who is in charge of beginnings and transitions. He is often portrayed as having two faces, one looking into the past “with memory” and another – into the future “with foresight”. This duality somehow reminded of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice that I am sharing below. This a moving tale of the power of love and music as its hero journeys to the Underworld to try to bring his beloved back to life.

Review: The Medici by Paul Strathern

The Medici [2003] – ★★★★1/2

The Medici. No other family in history stirs the imagination as much while, at the same time, inducing so many contradictory feelings—awe, amazement, trepidation. One of the most powerful and influential families in history, the Medici ascended from banking experts to the height of papal rule and European royalty, an astounding achievement. Their contribution to the Renaissance movement was unparalleled. Based in Florence, then an independent republic, they were overseeing the works and being behind the scenes of most major Renaissance projects, from Brunelleschi’s Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore to Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, influencing and/or providing finance to such major Renaissance figures as Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Rafael, Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei, and others. Paul Strathern’s book traces the family’s ascend and fall, zooming in and out of major events that shaped the course of Italian and European history. This non-fiction laces historical information with interesting trivia, being an almost perfect blend of insight and entertainment.

Continue reading “Review: The Medici by Paul Strathern”Review: King, Queen, Knave by Vladimir Nabokov

King, Queen, Knave [1928] – ★★★★

This is Nabokov’s second book, written in Russian in Berlin in 1927 when he was 28. At first glance, the novel may appear to be a rather banal take on a bourgeois love triangle, but Nabokov’s inventive use of language, his obsession with minute details to capture moments in time, and his uncanny humour all soon unveil a curious story with deep psychological portrayals, moments of delicious suspense, and one unpredictable ending. The plot revolves around one young man from the provinces named Franz Bubendorf, who comes to Berlin to work for his “uncle” and successful businessman Kurt Dreyer. Franz becomes immediately smitten with Dreyer’s beautiful young wife Marta, and his love is returned, but, barricading their path to happiness, is always the ever-present, annoying and “permanent” Dreyer. Will the couple find the way to be together, while also enjoying Dreyer’s hard-earned money?

Continue reading “Review: King, Queen, Knave by Vladimir Nabokov”Autumnal Trip to Paris

I have just got back from my (and my twin brother’s) birthday trip to Paris, and I thought I would share some highlights. The weather was surprisingly warm, and my family and I enjoyed the city’s autumnal foliage, tucking into our French onion soups, and just wondering around Paris at this time of the year. Below are the four cultural stops I made during this trip.

Continue reading “Autumnal Trip to Paris”Chopin: Favourite Ballades

I got inspired to write this post by the recent International Chopin Piano Competition held in Warsaw, Poland. Chopin’s four ballades are among the most beautiful of his works, and my favourites among the four have been shifting over the years. Currently, my favourite is Ballade No. 3 in A♭ major, Op. 47. Chopin dedicated it to his pupil Pauline de Noailles (1823–1844), and it is said to be inspired by Adam Mickiewicz’s poem Undine. I love this ballade for its sophistication and thematic shifts.

I love the interpretation of it by Polish pianist Krystian Zimerman (1956-), the winner of the IX International Chopin Piano Competition in 1975. Although his take is considered now quite restrained and conservative, I still prefer it over modern versions because the ballade already has quite a number of eccentric, expressive elements, and it is Zimerman’s understated precision that brings the best in it without overdoing it or distracting.

Enigmatic Paintings: Salem

Salem (1908) is a painting by English artist Sydney Curnow Vosper (1866-1942), who is mostly known for painting landscapes and people of Brittany. It depicts Welsh lady Siân Owen (real person, then aged seventy-one), dressed in traditional Welsh costume, attending a service at Salem Baptist Chapel in village Pentre Gwynfryn, Wales. The painting gained notoriety after some pointed out that Siân Owen’s shawl hides the face of the Devil (see the picture below where possible facial contours are outlined). Vosper himself denied his intention of the Devil in the artwork.

The Departure of the Train by Clarice Lispector

The Departure of the Train [1974/2015] – ★★★★★

This is Clarice Lispector’s short story about two women who board a train at Rio de Janeiro Central Station. They are strangers to one another, and find themselves on “opposite sides of life”. Dona Maria Rita is an aging widow, who has seen everything in her life and now is going to her son’s farm “to spend the rest of her life there”, while Angela Pralini is an independent, vivacious young woman who begins a new life chapter since she has recently broken off her passionate relationship with one cerebral Eduardo (“because you can’t prolong ecstasy without dying”). She is going to spend time with her aunt and uncle in the countryside, and is looking forward to this new adventure and simple life on the farm. We read these two women’s contrasting thoughts as they ride in a shared train carriage.

Continue reading “The Departure of the Train by Clarice Lispector”Nabokov’s Pale Fire: An Illusion Within an Illusion

Pale Fire [1962] – ★★★★★

Pale Fire is one of the most inventive and original literary works of the twentieth century. On the face of it, it is nothing more than a 999-line poem titled Pale Fire by poet John Shade, presented with extensive commentary by self-appointed editor Charles Kinbote. But, dig deeper, and there emerges a narrative full of red herrings, secret meanings, and psychological and philosophical insights into the nature of authorship, interpretation, and truth. Erudite academic Charles Kinbote and now deceased brilliant poet John Shade were apparently acquaintances and neighbours, and, by publishing a commentary to Shade’s work, Kinbote desires nothing more than to pay a touching tribute to his dear friend. But, is it really what it is, or there are other hidden motivations behind his work on Shade’s poem? In his commentary, Kinbote veers off on his own paranoid obsessions with Shade, the manner of his death, and his own country of Zembla. At every turn in his work, Nabokov encourages us to read between the lines, question narratives (what is reality and what is fantasy?) and try to find the truth by ourselves. Below, I will try to see the novel through the four “illusions”: (i) the illusion of objective literary criticism; (ii) the illusion of language; (iii) the “illusion (delusion) of grandeur”; and (iv) the illusion of identity.

Continue reading “Nabokov’s Pale Fire: An Illusion Within an Illusion”Sudden Light by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Sudden Light

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell:

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sighing sound, the lights around the shore.

Japan’s Autumn Moon Festival: Sakuraco Box Experience

Continuing with my Japan theme from the previous post, my readers probably know that I study Japanese and am interested in Japanese culture, but being away from Japan, it is hard at times to feel connected to the country. But, there are ways to do so, and one of them is through “Japan experience” sold in a box. I have already gushed about the Sakuraco box experience in my other post, and am now fortunate enough to be gifted a Sakuraco box for review. This is a monthly Japanese subscription box that includes traditional Japanese snacks, teas, and tableware. Each month features a different theme, and the box is especially irresistible this month since the Autumn Moon Festival is upon us, and in Japan, it means tsukimi (moon-viewing festivities). This is the most tranquil and mysterious of seasons that, among other activities, involves the poetic contemplation of Harvest Moon.

Review: The Man Who Died Seven Times by Yasuhiko Nishizawa

The Man Who Died Seven Times [1995/2025] – ★★★

Who doesn’t like a time-loop in their fantasy story? The idea that one can go back to the past and relive it, changing it or gaining particular insight from it is irresistible for fiction lovers. In novels The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North and Replay by Ken Grimwood, there are people who have a chance to relive their lives, and such films as Back to the Future and Groundhog Day popularised the concept of time-travel/loop in action and romantic comedies. Of course, the most famous example of a time-loop in detective fiction now is Stuart Turton’s The 7½ Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, and in Japanese fiction – probably still a light novel by Hiroshi Sakurazaka titled All You Need Is Kill (later Hollywood film Edge of Tomorrow). Since Nishizawa’s book of 1995 predates Sakurazaka’s light novel of 2004, it was one of the first in Japan to break into the market with the theme, and the idea of mixing sci-fi time-loops and a detective mystery. Now, it is published for the first time in English under the title The Man Who Died Seven Times, translated by Jesse Kirkwood.

Continue reading “Review: The Man Who Died Seven Times by Yasuhiko Nishizawa”10 Book-Music Pairings

I have recently read a number of articles on book and music pairings, including by Richland Library and Cassava Republic Press (where they paired (perfectly!) Nina Simone’s feverish Sinnerman with Baldwin’s novel Go Tell It On the Mountain), and decided to compile my own list (in no particular order). Literature and music at times make a perfect pairing, and in the list below, I tried to capture the similarities in both theme and mood. The music below is diverse, from classical to rock, J-pop and jazz.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

The paired music: Masquerade – Ballet Suite: 1. Waltz by Aram Khachaturian

My Reasons

Initially envisioned for the production of Mikhail Lermontov’s play Masquerade, this piece of music was turned into an orchestral suite in 1944. I think its sweeping, almost violent theme is suitable to describing Anna Karenina’s inner world of burning, overwhelming passion for Count Vronsky in Tolstoy’s story of one complicated love affair. That whirlpool of abundant, conflicting emotions comes to its climax as Karenina watches Vronsky compete in a horse race. The masquerade theme is also fitting here as Karenina and Vronsky have to wear masks of indifference in their daily life.

listen to the composition – buy the book

Continue reading “10 Book-Music Pairings”A Trip to York, England

I have just come back from my amazing trip to York, and am sharing my highlights. Founded by the Romans in 71 AD and previously being a Viking stronghold (from 866 to 954 AD), York proved to be a city with a hundred things to do, much more than I expected. There is a lot to explore, from the historic York (the thirteenth century cathedral and city walls) to the funky and unusual York (Wizard Tours, and shops dedicated to ghosts and cats). Below, I detail the stops that I made on my trip, and will also recommend food & drink establishments, as well as give some travelling tips.

Japanese Book Covers (Favourite Books)

This will be my 500th post, and I thought I would do something different. I have recently been exploring world literature translated to Japanese, and have stumbled upon some beautiful book covers I want to share. The general tendency of Japanese book covers seems to be either intricate, detailed artworks or minimalist designs, with few covers falling somewhere in between. The book covers below appear to fall into the former category. You can see that many Japanese book covers favour the long distance/panoramic perspective, rather than one focusing on the individual being the centre as western book covers usually do. This is an echo of Asian philosophy that we are all part of the whole, a community, being interconnected.

The stunning Japanese edition of Umberto Eco’s historical novel The Name of the Rose (on the left) depicts artworks from Beatus of Liébana’s The Commentary on the Apocalypse (commentary on the biblical Book of Revelation) written around 776. There is a number of copied versions of this manuscript, and, in particular, the first book cover above is the Vision of the Lamb, the Four Cherubim and the Twenty-Four Elders from the 1047 version painted by Facundus. As book covers, these are excellent choices because they capture the mystery, monastic life and the religious folklore of the novel.

Continue reading “Japanese Book Covers (Favourite Books)”Review: Grand Hotel by Vicki Baum

Grand Hotel [1929/2016] – ★★★★★

Like Vera Caspary’s Laura and Luigi Bartolini’s Bicycle Thieves, Grand Hotel is yet another novel that is likely best known as its ecranisation – the 1932 Oscar-winning film Grand Hotel, starring Greta Garbo, John Barrymore and Joan Crawford. And, indeed, the story is cinematic. Austria-born author Vicki Baum puts at its centre one of the most intriguing tourism inventions of the late nineteenth century – a grand hotel that, in its heyday, was the pinnacle of travelling luxury, providing all kinds of exclusive comforts for its rich clientele under one roof, creating “a home away from home”, and catering for each of their guests’ whims, rather than passively accepting them into the accommodation. Into this already intriguing institution, Baum puts the most diverse characters, from one capricious aging ballerina to a lowly bookkeeper suffering from an incurable illness who just so happens to find himself amidst all the luxury thanks to his life savings. Together, this cast of curious characters presents a microcosm of the Berlin society of the mid-to-late 1920s, a roller-coaster period of changes characterised by the questioning of moral norms and the gender roles shift. By juggling her colourful characters and their situations so skilfully in the novel, Baum delivers one of a kind, part tragic part comic exposé of lives lived.

Continue reading “Review: Grand Hotel by Vicki Baum”The Caravan’s Bells

“Love and patience do not go together.

Reason cannot stop your tears./

Ecstasy is like a beautiful town

that cannot be controlled

by any one of its inhabitants./

The caravan of life is passing us by,

but no one can hear the sound of the bells.”Rumi

Rumi (1207-1273) was a poet, Sufi mystic, faqih, and theologian. Written largely in Persian, his poetry reflected the teachings of Sufism on love, unity, and spiritual enlightenment.

Review: Gourmet Rhapsody by Muriel Barbery

Gourmet Rhapsody [2000/09] – ★★★★

Muriel Barbery rose to international fame with her bestseller The Elegance of the Hedgehog, a quirky novel that revolves around one Parisian apartment block and its concierge Renée Michel. But, before The Elegance of the Hedgehog, Barbery published her debut Gourmet Rhapsody, which is as unusual an offering, and would also delight fans of extravagant, charismatic narrators. Pierre Arthens is a world-renowned food critic, but is now on his deathbed, craving that final forgotten taste that eludes again and again. He looks back on his life full of culinary discoveries and pleasures, as people he once knew also have their say on the man and his place in their world. With the economic ingenuity of a sumptuous three-course meal in some upscale French restaurant, Barbery delivers a different perspective and much food for thought within each of her elegantly presented short chapters.

Continue reading “Review: Gourmet Rhapsody by Muriel Barbery”The Penguin Book of French Short Stories

The Penguin Book of French Short Stories is comprised of two volumes, and the first volume spans almost 400 years, from the 16th century to the fin de siecle. As with my review of The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories, I am focusing on just six stories from this collection of more than forty. If The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories revolved around limitations, hardships or eccentricities, then it can be said that many stories in The Penguin Book of French Short Stories are all about absurdities, lost chances, and strange phenomena.

A Passion In The Desert by Honoré de Balzac – ★★★★1/2

“…they ended as all great passions do end – by a misunderstanding. For some reason one suspects the other of treason; they don’t come to an explanation through pride, and quarrel and part from sheer obstinacy.’

This is a story about the French expedition in Upper Egypt. A French soldier is captured by a group of Arabs, and after escaping the “death march”, he finds himself all alone in a desert without a horse. He has already resigned himself to dying when he spots a sleeping panther, whose paws are covered in blood, sleeping next to him. As ever astute when it comes to human relation and unsaid emotion, Balzac concocted a curious story laced with suspense about a man’s relationship with a wild animal.

Continue reading “The Penguin Book of French Short Stories”Charles Kuwasseg: Coastal Life

Charles Kuwasseg (1833-1904) was a French landscape artist, and the son of Austrian painter Karl Joseph Kuwasseg. Once a sailor, he later received his formal training in art under Jean-Baptiste Durand-Brager and Eugène Isabey. Influenced by the Barbizon School, he painted land and seascapes around the coasts of Brittany and Normandy, and scenes of Paris. The four paintings below showcase his skill in evoking the atmosphere of life by the sea.

Buildings or dwellings near water often take the central stage in Kuwasseg’s works, and this further emphasises the intimate relationship of a man with the sea in his paintings. The buildings’ close proximity to water means that we can deduce that water and its mood govern virtually all the aspects of these people’s lives. In line with the Barbizon school, the realism here is offset by romantic artistic overtones. There is much colour, but also softness of form.

Continue reading “Charles Kuwasseg: Coastal Life”Mini-Review: The Cabinet by Kim Un-Su

The Cabinet [2006/21] – ★★★1/2

For the lovers of the incredulous and highly imaginative, this book details a number of extraordinary cases filed in Cabinet 13. The man in charge of the cabinet is Research Assistant Deok-geun Kong (the narrator), and even he does not know the full extent of the cabinet’s mystery or why the organisation known only as the “syndicate” is after it. There are medical mysteries here in the vein of Oliver Sacks (The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat), but completely fictitious, as well as Italo Calvino-inspired whimsy (see also The Musical Illusionist, a Borges-inspired book-encyclopaedia of fantastical curiosities that mixes facts and fiction). Deok-geun Kong’s boss is Professor Kwon, who is researching the world’s various “symptomers”, people who allegedly evolved “beyond humans” to the next phase, and are displaying surprising abilities or conditions. For example, there is a man who has a ginkgo tree growing out of his hand, a woman who has a doppelganger pestering her, and there are “time-skippers”, people who mysteriously disappear for days, months or even years only to reappear in distant places with no memory how they got there.

Continue reading “Mini-Review: The Cabinet by Kim Un-Su”7 Fiction Books About Anthropologists

There are not many fiction books out there about anthropologists, but those that do exist often shine with insight, erudition and thrills of a real adventure. Below are seven books featuring anthropologists who often grapple with the meaning of their profession and the ethics of their research. Their field-works take them to various continents and countries, from Papua Guinea to Thailand, and from Congo to Peru. Let’s hope writers will be more inspired to write stories featuring anthropologists!

The Storyteller by Mario Vargas Llosa

With the very sad passing of Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa (The Time of the Hero) this year, there has probably never been a more appropriate time to delve into his work and its meaning, and there has probably never been a more intriguing or colourful character-anthropologist than in Vargas Llosa’s novel The Storyteller (El Hablador). This is a story of brilliant man Saúl Zuratas and his obsession with the tribe of Machiguengas in the forests of Peru. Told at first from the perspective of his university acquaintance, this fiction book about anthropology then details Zuratas’s eventual transformation. Steeped in indigenous folklore and knowledge, the story raises many thought-provoking questions, including on the proper way to preserve indigenous tribes and their traditions, and on the role that the tradition of storytelling plays in indigenous cultures.

Continue reading “7 Fiction Books About Anthropologists”Review: The Kingdom of This World by Alejo Carpentier

The Kingdom of This World [1949/57] – ★★★★★

One always comes to Alejo Carpentier’s books with a kind of trepidation mixed with delicious expectation. The knowledge that threading through his labyrinth of prose will come with transcendental insights or unheard-of wonders makes his novels hard to resist. If I previously termed his novel The Lost Steps “a stimulating read of one extraordinary journey of self-discovery,” Carpentier’s The Kingdom of This World is a less introspective but also much more intense reading experience as the author turns his attention to the 1791-1804 revolution in Haiti, a place Carpentier visited in 1943. In turbulent Haiti, we see the world through the eyes of slave Ti Noël, whose master is squire and plantation owner M. Lenormand de Mézy. Ti Noël’s early idealization of one-armed man and mystic Macandal, the Mandingue, will eventually involve him in one of the world’s bloodiest revolutions. Mixing mythology, superstition, and the alleged cyclical nature of history, Carpentier takes no prisoners in this increasingly provocative, horrifying, but also absolutely enthralling novel of hell born of good intentions.

Continue reading “Review: The Kingdom of This World by Alejo Carpentier”The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories is an anthology of forty Italian short stories edited by Jhumpa Lahiri. It includes stories by such authors as Alberto Moravia, Natalia Ginzburg, Primo Levi, Italo Calvino (The Baron in the Trees), Elsa Morante (Arturo’s Island), Dino Buzzati (Catastrophe & Other Stories), Luigi Pirandello (Six Characters in Search of an Author), Cesare Pavese (The Moon and The Bonfire), and others. I am reviewing six of the short stories below, and they all seem to revolve around limitations, hardships or eccentricities.

Silence by Aldo Palazzeschi (translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell) – ★★★★1/2

“There was not a moment in the day when silence did not fill the place entirely; there was not a single nook or cranny that the silence had not filled with the imposing solemnity of its presence.” Eccentric, reclusive man Benedetto Vai seems to have taken a vow of silence because he does not utter even one word to anyone, not even to his housekeeper Leonia, and this state of affairs seems to have been ongoing for years and years. And, then, he starts to accumulate the finest cutlery that seems to exist in the world. Is he preparing for some feast, and will the house be finally filled with voices? Palazzeschi gets his reader’s attention effortlessly by presenting, and with much finesse, a very unusual character who has one strange lifelong whim. The melancholic cadence is not as strong, but there is still this clear message that, at times, the greatest fight in a person’s life is their fight with themselves.

Continue reading “The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories”Damascus Nights by Rafik Schami + Reading Around the World (Vol. 2)

Damascus Nights [1989/95] – ★★★★

German-Syrian author’s novel relies heavily on the Al-Qaskhun/Al-Hakawati or Storyteller tradition of the Middle East (think One Thousand and One Nights) to tell the story of one coachman Salim, who, inexplicably, lost his voice even though he is a gifted storyteller. The year is 1959, the place is Damascus, Syria, and Salim’s seven loyal friends started to devise ingenious ways to enable Salim to talk again. One of the solutions proposed is that each of Salim’s friends should tell him his own story, and when Salim hears them all, he would be able to speak again (“the curse of his muteness will be broken”). So, begins the whirlpool of fables blending seamlessly reality and fiction to one spellbinding effect, as each of Salim’s friends – locksmith Ali, geography teacher Mehdi, barber Musa, former statesman Faris, Tuma, the “emigrant”, café owner Junis, and once unjustly imprisoned Isam, all try to outsmart and outspeak each other. However, is Salim the cleverest and slyest of them all in the end?

Continue reading “Damascus Nights by Rafik Schami + Reading Around the World (Vol. 2)”Rafail Levitsky: Bridge in the Woods

This Sunday, I am sharing a lyrical, slightly unsettling Romantic artwork titled Bridge in the Woods by Rafail Levitsky. It depicts a wooden bridge over a ravine deep in a forest. A lone woman, dressed elegantly in white, stands on it, looking unsure. The natural light and the woman’s white dress give her a phantom-like appearance that contrasts drastically with the natural surroundings. The place is undoubtedly deep in some woods due to the dense vegetation and sparse natural light seen reaching the location. The precarious nature of the bridge and the woman’s proximity to its most unstable point give this otherwise serene artwork the element of slight unease. Metaphorically, the bridge may also function as a crossing to other, unexplored side of things, and its haphazard nature gives off a sense of risk/danger that follows any adventurous pursuit.

Continue reading “Rafail Levitsky: Bridge in the Woods”How I Study Japanese

I apologise for being absent from the site, and if this post is not of interest to every reader of my blog, but since I have now reached a strong intermediate stage in my Japanese-learning journey (yes, after years of study), I thought I would share some traditional learning resources which I found useful in my beginner stage of learning Japanese. I know that language immersion and listening to podcasts, Japanese YouTube, etc. is popular nowadays and very important, but here I will talk about some books that I personally found useful in my language-learning journey, and which I believe don’t get enough attention or promotion on the Internet.

First, I believe that the very best introductory textbook on the market for a Japanese learner is Minna no Nihongo (Books 1 and 2). This is the most thorough, the most detailed textbook for a beginner you can get. It may appear daunting at first since the textbook is in Japanese, but there is separate book you can buy that would explain the grammar in your native language and also translate everything in the text. What makes it so great is that it presents the material in the most logical and progressive manner with no big jumps or chaotic presentation of topics. This is very important for learning Japanese in particular – that there is logical, step-by-step progression in the presentation of grammar. Minna no Nihongo is also more detailed and provides much more words and grammar explanations than the Genki I and II textbooks, its main competitor. Moreover, the Minna no Ningono textbook has separate booklets available to practise each core skill – listening, kanji, writing, grammar and reading. For kanji (a hieroglyphical system that is part of the Japanese writing system), I also highly recommend the Kanji Look and Learn book, together with its workbook.

Continue reading “How I Study Japanese”A Poem by Emily Brontë

Today, I thought of sharing a five stanza-poem by Emily Brontë, the author of Wuthering Heights. It is titled “Often Rebuked, Yet Always Back Returning”, and despite its tenderness, showcases the author’s steely determination to seek freedom, follow her own inner voice, and forge her own path forward irrespective of all the scholarly dogma and independent of her sisters or society. Her creative realm would be a place neither wholly imaginary nor objectively perceivable, but still real, like her characters Heathcliff and Catherine’s emotional world, unseen by others, but still as real to them as any observable-by-others objective reality.

–//–//–//–//–// –

“Often rebuked, yet always back returning

To those first feelings that were born with me,

And leaving busy chase of wealth and learning

For idle dreams of things which cannot be:

Continue reading “A Poem by Emily Brontë”My Recent Trip to Paris: Cultural Highlights

I have recently returned from my trip to Paris, France and am sharing my highlights. Though the big attraction of my trip was the Musée de Cluny, there are some smaller, “off-the-beaten track” museums in Paris that I have also always wanted to visit, and I present two of them at the end of my post.

- Musée de Cluny

Address: 28 Rue du Sommerard, Latin Quarter, Paris; Metro: Cluny – La Sorbonne. Admission: Ticketed.

The Museum of the Middle Ages is one of the largest collections of medieval art and artefacts in Europe, and is located in the former town-house of the Abbots of Cluny, which also has elements of Gallo-Roman ruins. It has medieval sculptures, tapestries, metal-work, carvings, religious, household and war items, and stained-glass examples on displays. My highlight was, of course, The Lady and the Unicorn series of tapestries, which I have wanted to see for a long time. The beautiful tapestries, with elegant depictions of animals and plants, were woven in the late fifteenth century, and each represents one of the five human senses: touch, sight, hearing, smell and taste. The sixth tapestry, titled A mon seul désir, is said to represent the sixth sense of the heart or intuition.

Continue reading “My Recent Trip to Paris: Cultural Highlights”The Enchanted Garden

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844–1927) was a talented British Pre-Raphaelite painter who painted scenes from Dante’s Divine Comedy, Boccaccio’s poetry, mythology and other areas. I am particularly attracted to her artwork The Enchanted Garden because it features one of my favourite themes in folklore on which I also previously wrote this post – the so-called “impossible task”, and in this case, the one going against the rules of nature (see also Czech fairy tale The Twelve Months).

Continue reading “The Enchanted Garden”The Penguin Book of Dutch Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Dutch Short Stories is an anthology of thirty-six Dutch short stories spanning almost a century and edited by Joost Zwagerman. The majority of the stories appear in the English translation for the very first time, and I am reviewing five of them below.

The Opera Glasses by Louis Couperus (trans. Paul Vincent) – ★★★★1/2

This is a very well-written short story that keeps you on your toes throughout. It is about a young man in Dresden who decides to go and see Wagner’s opera The Valkyrie in theatre one night. He thinks he needs some opera glasses and hastily buys some heavy ones from one sinister-looking optician. What follows when he takes his theatre seat is one bewildering turn of events that even he cannot explain, and it concerns his sudden urges, obsessions and audience fixations. The object in his hands – those heavy opera glasses – may be the cause. Louis Couperus (1863- 1923), one of the renowned Dutch authors, weaves into this effective tale of a “haunted” object the themes of fatalism, premonition, and obsessive thought.

Continue reading “The Penguin Book of Dutch Short Stories”Thomas Hardy: 3 Short Stories

Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was an English novelist who wrote such classics as Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Far from the Madding Crowd, Jude the Obscure, and The Woodlanders. He was also a poet (Wessex Poems) and short story writer. Hardy’s collection of ten or so short stories is compiled in The Fiddler of the Reels & Other Stories, Penguin Classics, and I am sharing my thoughts on three of them from this collection below. These are tales of romance, tragedies, and fate working in mysterious ways.

The Fiddler of the Reels [1893] – ★★★★

“Crowds of little chromatic subtleties, capable of drawing tears from a statue, proceeded straightway from the ancient fiddle, as if it were dying of the emotion which had been pent up within it ever since its banishment from some Italian city where it first took shape and sound…” (Thomas Hardy).

This is a story about eccentric fiddler “Mop” Ollamoor who can make any woman swoon with his almost devilish in its effectiveness fiddle-playing, and one of the “victims” who fell for his charm is young woman Car’line Aspent of Stickleford, who is already engaged to Ned Hipcroft, a mechanic. What began as one-sided romance soon morphed into something else – something more. We see in this story Hardy’s common love triangle – a woman chooses between a down-to-earth, hard-working man of practicality (Ned) and a visually-striking, albeit unreliable, man of shiny appearances and whimsies of all kinds (“Mop”). Hardy writes with elegance, passion and humanism, and this heart-breaking story, that is also set against the backdrop of the Great Exhibition of 1851, reminds very much of his other, heavier tragedies. Even in his short stories, Thomas Hardy can provoke us, surprise greatly, and deeply move.

Continue reading “Thomas Hardy: 3 Short Stories”Vasily Vereshchagin: The World Tour

Vasily Vereshchagin (1842-1904) was a Russian artist, writer, traveller and collector famous for his detailed artworks of world cultures, and by-that-time unorthodox paintings of war. Born in a family of nobility, he was enrolled into a military school as a boy (as was expected of his family’s standing), but his passion was painting, so he also studied art at the Academy of Art in St. Petersburg and under French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris. He was later accepted to be a war artist in Samarkand, and much later lived in India, and travelled extensively all over Europe, Asia and America, while continuing to paint prolifically. Below are some of Vereshchagin’s paintings that showcase his incredible observation of other countries’ architecture, traditions and modes of life.

Japanese Woman, 1903; A Buddhist Lama at Pemionchi Monastery, 1875; Japanese Beggar, 1904 by Vasily Vereshchagin.

Continue reading “Vasily Vereshchagin: The World Tour”Ferdinand Hodler: Symbolism II

Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) was a Swiss symbolist painter known primarily for his enigmatic depictions of people and surrealist scenes, but he also produced striking realist land and waterscapes. His artwork aims to penetrate the mysteries of the natural order, universe, and our own minds. The three paintings below, which are the continuation of my previous post Ferdinand Hodler: Symbolism I, present Hodler’s curious philosophy, and ideas of life renewal and spring.

South Korea: 5 Intriguing Short Stories

Miss Kim Knows [2021/23] by Cho Nam-Joo – ★★★★

In this short story collection, Cho Nam-Joo (Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982) focuses on the lives of eight Korean women, showcasing issues in contemporary Korea. In the titular story, even before starting her first day at her new job in a hospital advertisement agency, a young woman gets more than an eyeful of that company at an organised workshop for employees hosted over a weekend. Her predecessor, mysterious Miss Kim, a lowly employee, seems to have run the agency almost single-handedly, but where is she now and what happened to her? Cho Nam-Joo’s story idea and its beginning are definitely much stronger than the somewhat underwhelming finale, but this is still one memorable “a person against the system” tale that provides an incisive, humorous insight into the workings of a Korean company filled with nepotism and incompetence. I read this short story in Miss Kim Knows and Other Stories by Cho Nam-Joo [translated by Jamie Chang, Scribner UK, 2023].

The Glass Shield [2006/23] by Kim Jung-hyuk – ★★★★

Translated by Kevin O’Rourke, this is a story of two inseparable young men (our narrator and M) who go to a series of job interviews together because they cannot bear the thought of not working for the same company. They try very unconventional techniques to impress their interviewers (including untangling a yarn), but because of their togetherness and unique interviewing style, they have had no luck so far landing anything. That is, until the two friends-pranksters become an internet sensation, and finally have a chance to shine in the crowded job market. This story brims with comic originality, and is about trying to triumph through one’s eccentricity and individualism in a big city governed by monotony and predictability. It ends on the reconsideration of one’s life purpose. The story is part of The Penguin Book of Korean Short Stories [edited by Bruce Fulton, Penguin Classics, 2023].

Continue reading “South Korea: 5 Intriguing Short Stories”Chabouté: To Build a Fire

To Build a Fire [1902/2007/18] – ★★★

Based on short story To Build a Fire by Jack London, this graphic novel by French artist Christophe Chabouté (Alone, Moby Dick) recounts one day in the life of a man newly arrived to north-western Canada as an ardent prospector in search of gold. The year is 1896, and our man is just one of many finding their feet in the environment of bitter cold (minus fifty), treacherous ice lakes, and few provisions. His dog is his only companion, but, otherwise, he is alone, making his way to his mates’ camp.

This is a survival story that emphasises the importance of fire and of making fire to survive in inhospitable conditions. The man was told many times how dangerous it is to travel alone in such freezing temperatures, but he is sure of himself, or is he? The story is also about the arrogance and presumptuousness of the mankind who think they can outsmart Mother Nature. The man in the story learns his lesson, but at what cost?

Continue reading “Chabouté: To Build a Fire”St. Valentine’s Day

“Love is always love, come whence it may. A heart that beats at your approach, an eye that weeps when you go away are things so rare, so sweet, so precious that they must never be despised“. Guy De Maupassant, Miss Harriet

Review: The Rainbow by Yasunari Kawabata

The Rainbow [1951/2023] – ★★★★

Some notable Japanese authors, including Tanizaki in The Makioka Sisters and Dazai in The Setting Sun, captured the traumatic, directionless period of Japan just after the WWII, and this is Kawabata’s contribution in distilling a curious period of time that was also not without a hope for the future. This is a story of architect Mizuhara and his two daughters by two different mothers, older and rebellious Momoko, and younger and dutiful Asako. Asako has just returned from Kyoto after searching for her other half-sister Wakako without her father knowing. As the family embarks on a travelling tour around Japan’s changed-by-the-war sights, unexpected meetings from the past open old wounds. There is suddenly a realisation that a distance between one’s heart and the next may be light years away, while the track from one’s heart to the past is just a blink of an eye. This unassuming story of one fragmented family is, nevertheless, full of surprising emotional depths.

Continue reading “Review: The Rainbow by Yasunari Kawabata”7 Great Epistolary Novels

First of all, I would like to wish all my followers and readers a very Happy New Year (Year of the Wood Snake 🐍), and may this year bring each of you only the best. I think it is also fitting to open this year with some thoughts on books that detail correspondence or messaging, often signalling renewed hope or intrigue in books. Why would some authors pen their books in the epistolary format (in the format of a letter(s))? What is the meaning of this book format, and what purpose it serves? Below are 7 books that were written using this curious technique.

This format has many purposes and aims depending on a book and plot, for example to open a world from a curious perspective, but books where characters pen letters may also give an impression that these characters somehow would like to take the reader into their confidence, and, possibly, make them psychologically complicit in these characters’ thoughts and deeds. Letters, like diaries, in novels may also carry a purpose of eliciting sympathy for whoever writes them, and this is especially beneficial in plots where the main character is not altogether likeable, like Lady Susan below. At times, “epistolary” also means a novel written in a diary-format (Edith’s Diary, The Liar), but for the purposes of this list, I will only talk about letters and correspondence.

Lady Susan by Jane Austen

Lady Susan is probably the best-known example of a book written entirely in the format of letters. It suits the comedic plot, too, since the perspective is from charming, mischievous, slightly devious Lady Susan. She is a widow, and from her letters to her distant relatives and in-laws we deduce that she would like to maintain her luxurious style of living despite having “fallen on hard times”. She is after a husband yet again, and not only for her, but also for her daughter Francesca. The letter-format of this novel keeps us in suspense and also allows us a glimpse into the mental gymnastics of the main character, who has to survive through cunningness and deceit if she is to maintain her societal status.

Continue reading “7 Great Epistolary Novels”Doctors of the Past: Satirical Medical Art

“…I curse loquacious doctors for their lies:

They kill the man who’d live, save him who’d died.

Many physicians are foes of the sick

And fail to study what is wrong but, quick,

Prescribe a cure, and often kill outright…”

Part of a medieval Latin poem, discovered D. Yates, Bulletin of the History of Medicine (1980).

Satirical medical art has been around a long time. For example, caricatures of the medical profession, quacks and healers, are found in the sixteenth century Italy, and, then, English painter William Hogarth (1697–1764) also brought to the public his vision of the medical practitioners’ faults, as well as the horrors of Bedlam. Below are three paintings from three different historical periods, showcasing the prevalent attitudes towards medical profession or the state/progress of medicine.

Continue reading “Doctors of the Past: Satirical Medical Art”“Double Trouble”: 7 Fiction Works About Identical Twins (Part II)

I have recently finished a wonderful, much under-read novel by Wilkie Collins titled Poor Miss Finch that focuses on a mysterious pair of identical twin brothers who court one beautiful girl in one small village in East Sussex, UK, and, thus, got inspired to write this post. It is the continuation of my previous post – “Double Trouble”: 7 Books That Focus on Identical Twins, where I talked about works of such authors as Christopher Priest and Hanya Yanagihara, and since that time have read a number of other books about twins. Though identical twins as side characters are more or less a well-known, permanent fixture in literature (Harry Potter, Gone With the Wind), there are actually some great books out there that have them as intriguing lead characters, too.

Poor Miss Finch [1872]

Inspired by his own short story The Twin Sisters [1852], Wilkie Collins wrote Poor Miss Finch in 1872. The tale is about one strong-willed French woman, Madam Pratolungo, who becomes a companion to a beautiful blind girl living apart from her extended family in a small village of Dimchurch in East Sussex. This girl, Lucilla, falls in love with a dashing young man Oscar Dubourg, but he has a more confident and outspoken identical twin brother Nugent, who may also have strong feelings for Lucilla. When Oscar’s appearance changes, and there is also a prospect that Lucilla may recover her sight, Nugent senses that it may be time to make his move. The plot revolves around one preposterous turn of events and there is some melodrama, but this is still a fine page-turner of a novel with vivid characters (including little “vagabond” girl Jicks and eccentric doctor Herr Grosse), bold themes, and delicious psychological aspect of a rivalry between two very different brothers.

Continue reading ““Double Trouble”: 7 Fiction Works About Identical Twins (Part II)”Saint Augustine

Saint Augustine or Augustine of Hippo (13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was born on this day in 354. He was a philosopher and a bishop whose writings influenced Western philosophy and Christianity. His works include The City of God, On Christian Doctrine, and Confessions. Below are some of his quotes.

“Faith is to believe what you do not see; the reward of this faith is to see what you believe.”

“The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page.”

“Do you wish to rise? Begin by descending. You plan a tower that will pierce the clouds? Lay first the foundation of humility.“

Continue reading “Saint Augustine”Hans Baldung: The Knight, the Young Girl, & Death

Happy Halloween! 🎃 Among many spooky memento mori paintings, Hans Baldung’s The Knight, the Young Girl, & Death must be one of the most memorable. In this artwork, the knight and the lady are making their getaway from the skeleton, representing Death, that bites on the girl’s dress. The girl has her arms around the knight, and hides her face in fear. She is positioned between life and happiness (represented by the knight), and death and total destruction (represented by Death). The knight and the girl are both young and represent “unity”, being both dressed in red, but Death does not differentiate who to take. The vigour and energy of the knight’s horse further underscore the contrast between life and debilitating Death that is on the ground and also mirrors and mocks the girl’s hug by embracing a tree stump. Hans Baldung (1485-1545) was the most gifted student of Albrecht Dürer, a German artist of the Renaissance period, and was also a talented engraver, printer, and stained glass painter.

Review: Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig

Burning Secret [1911/2008] – ★★★★1/2

“I have lived a great deal among grown-ups. I have seen them intimately, close at hand. And that hasn’t much improved my opinion of them.” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Stefan Zweig knew that authentic drama, horror, trauma may simply reside in one’s realisation of personal circumstances, situation, predicament. The story in this psychologically astute novella takes place in Semmering, Austria. When one dashing dandy, a baron, stops at a resort all alone, he is ready for his next romantic conquest partly to ward off the boredom in this place. He is young, but already an expert womaniser, and his gaze falls on one beautiful woman who also happens to be with her twelve year-old boy. The Baron’s pursuit of the woman starts through befriending that boy called Edgar, but the Baron does not even realise the dangers behind sowing so many seeds of attachment, as Saint-Exupéry also wrote in The Little Prince: “you become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed“.

Continue reading “Review: Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig”Japanese Short Stories from Tanizaki, Shiga, Seirai, Ogawa, & Nakajima

I. Longing [c.1917] by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (trans. Paul McCarthy) – ★★★★

This is one dreamy, evocative and progressively eerie narrative of a seven-year-old boy on a journey through the dark countryside surrounded by “white, fluttering things”. He spots a house in the distance and thinks it is his home, only to be confronted with one nasty, unwelcoming version of his “mother”. Then, he hears the sound of a shamisen coming from somewhere deep inside the surrounding pine forest.

Though the end strongly suggests that this is a story of a boy/man who tries to come terms with a trauma surrounding his mother or her (new) attitude towards him, it may also be a story of a boy who tries to make sense of his new situation (his family got poorer and migrated to the countryside), or a parable of a child who first glimpses the frightening prospect of existence independently from his mother. Either way, there is certainly there a metaphor of a struggle one undergoes to find moments of hope and happiness in a life that presently appears full of heartache, confusion or despair. I read this short story in Longing and Other Stories by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki [translated by Anthony Chambers and Paul McCarthy, Columbia University Press 2022].

Continue reading “Japanese Short Stories from Tanizaki, Shiga, Seirai, Ogawa, & Nakajima”Japanese Fiction: Schoolgirl, & The Little House

Schoolgirl [1939/2011] by Osamu Dazai (trans. Allison Markin Powell) – ★★★★

The green of a May cucumber has a sadness like an empty heart, an aching, ticklish sadness. Schoolgirl is a short novella where we follow the thoughts of one Japanese schoolgirl for just one day, from the moment she opens her eyes in the morning (“Almost the same. Absolutely empty”) to her concluding “Goodnight”. While she exhibits the usual teenage angst, telling us of her frustrations, anxieties and insecurities, tinged with doses of depression and apathy, her existence also momentarily turns to true delight as she finds small things to appreciate around her throughout the day.

As usual, Dazai (No Longer Human) holds a mirror to the Japanese society, and its fault are glaring as seen through the eyes of this slightly haughty, self-absorbed teenage girl. We become privy to her curious train of thought that also indirectly ridicules the societal hypocrisy and conformity. It is a very short novella with highly personal musings, but Dazai’s usual broader themes of shame, alienation and identity are also clearly sticking out. Though young, the schoolgirl is already experiencing some kind of an existential exhaustion, as well as searches for her identity, awakening to all the flaws around her and inside her, and even pining for the past when her sister still lived in the house and her father was still alive. While trying to win the affection of her distant mother who devotes herself to others, the heroine also wonders what it would take for her to preserve her sense of individuality in this society so clearly obsessed with conforming to the expectations of others and “keeping up appearances”. Will this attempt to stick to the ideals of her childhood be worth it at all in the end?

Continue reading “Japanese Fiction: Schoolgirl, & The Little House”NYT’s Best Books of the 21st Century: Some Thoughts

This summer, The New York Times (NYT) published list “100 Best Books of the 21st Century”, compiled from a survey of “hundreds” of novelists, non-fiction writers, academics, editors, journalists, literary critics, publishers, etc. (you can see the full list of the titles here since the original list is on the other side of the paywall). I am late to comment on this, but because I had to be absent from this site this summer, I thought I would do so now, since I also enjoyed reading takes on it over at The Book Stop and The Reader’s Room. I do understand all the drawbacks of such lists, and my point is not to put down any undoubtedly great books or authors featured on this list, but just comment (i.e. rant) on the list overall.

Continue reading “NYT’s Best Books of the 21st Century: Some Thoughts”J. S. Bach: Keyboard Concerto No. 1 in D minor

Today (25 September) marks 92 years since the birth of Glenn Gould (1932-1982), a famous Canadian pianist and renowned Bach interpreter, so I would like to share the following recording of Gould playing Allegro from J. S. Bach’s musical masterpiece Keyboard Concerto No. 1, one of my all-time favourite pieces, which is also said to be inspired by Vivaldi’s Grosso Mogul. Incidentally, 25 September is also the birthdate of composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) (see my other post on his sublime Piano Concerto No. 2).

Novels That Resemble Films By Hitchcock, Lynch & Burton

Have you ever wished they were some great novels in existence so that you can again experience the atmosphere or tropes of your favourite films in a literary form? Below are lists of novels that display Hitchcockian, Lynchian and Burtonian trademarks, conveying these directors’ spirit and unique vision. To make these lists more interesting, I have decided not to include novels that became these directors’ films, but highlight others with a similar ambiance or elements.

Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) 🔪

- A great British film director and a true “master of suspense” who built tension in his films through numerous innovative cinematic techniques; notable films include: The Birds, Psycho, Vertigo, Rear Window, Dial M for Murder, Rope, Spellbound, & Rebecca; some of his cinematic “trademarks” include:

- Ordinary people thrust into mysterious or dangerous situations

- Voyeurism and surveillance

- An innocent man accused

- Characters ending up switching sides

- Mistaken identity

- Single-location settings that increase tension

- A climatic plot twist, etc.

Short Stories: “The Green Lamp”, & “The Man Who Planted Trees”

The Green Lamp [1931] by Alexander Grin – ★★★★1/2

This short story begins in London, 1920. John Eve, a jobless and penniless young man, finds himself at the lowest point in his life in the city in the middle of winter. John has practically nowhere to go when he hears a proposition made to him in a bar from one rich stranger named Stilton. That man offers John ten pounds a month if John would rent a room in one unassuming building with a view to the street, and then would simply light a lamp covered by green cloth so it can be viewed from the street. John has to do this seemingly meaningless routine every day from five to twelve in the evening, just burning an oil lamp. Stilton then promises John that this would be his indefinite, paid “occupation”, and, in some months or years, perhaps some influential people would come and make John rich.

Continue reading “Short Stories: “The Green Lamp”, & “The Man Who Planted Trees””Evelyn De Morgan: Spiritual Symbolism

Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) was an English post Pre-Raphaelite painter, whose art reflected her beliefs in spirituality, mythology, feminism, pacifism, and other areas. The wife of potter, novelist and designer William De Morgan (1839-1917), Evelyn attended the Slade School of Art before moving away from the classical genre to the Pre-Raphaelite movement under the influence of George Frederic Watts (Hope), his students, and such Pre-Raphaelite painters as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt. I love interpreting De Morgan’s art as a spiritual journey of the soul or through the prism of symbolism, and hence the title.

The Love Potion by Evelyn De Morgan

The Love Potion is a curious painting because it aims to reverse the usual presentation of a sorceress in art. A woman, dressed in a golden gown, is seen brewing a love potion in her study. Though a cat, a clear symbol of dark magic, is seen beside the woman, her surrounding alchemical books clearly indicate that she is not some run-of-the-mill witch, but a scholar, a person of much intelligence and skill. The sorceress’s calm demeanour and profiled position signal authority and respect. Her actions are to be taken seriously. By presenting the sorceress in a yellow attire, De Morgan also suggests that she has already attained one of the final stages of the alchemical process (represented by the golden colour), and now is close to final salvation and enlightenment. The other main colours of the alchemical process of the soul transformation (black (green), white, and red) are also prominent here, hinting to us that this artwork has a deeply symbolic meaning. It is clear, though, that her potion has something to do with personal matters of love as a loved-up couple is seen outside her window (perhaps the sorceress is intent on breaking up the lovers?)

Continue reading “Evelyn De Morgan: Spiritual Symbolism”10 Classic Stories About the Fall of the American Dream

The idea of the American Dream has been the cornerstone of the United States, the American way of life and experience. It has been an enduring emblem representing hope for the future, prosperity, and success for its hard-working citizens, and an ideal to reach for ardent new-comers, believing in the variety and richness of opportunities on offer in their new home-land. But, what does this concept really mean, and how it has been transformed in changing times? Also, what happens when it all goes wrong?

The US Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal”, with each person having a right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”. However, as the Great Depression (1929-1941) showed, millions of even hard-working men and women of steely determination are not immune to sudden poverty, horrid destitution, and utmost ruin. Moreover, the grind of the wheels of capitalism can produce ruthless behaviour, resulting in the emergence of inhumane and horrendous-for-people environments, as Sinclair wrote in The Jungle. Nevertheless, though facing poverty, people could still have their “American Dream”, as in “hope”, in their hearts. All that began to change from the mid-1940s, when the concept of the American Dream started to be equated with monetary success only. It is at this point that both of its definitions began to crumble for good, as disillusioned people started chasing their own tails, as, in turn, their ideals turned out to be well-constructed mirages.

Many stories were written from various perspectives that detail the so-called “Fall of the American Dream”, both before and during the 1920s, during the Great Depression, and also after the World War II. Below are some classic story examples (with some plot spoilers in their descriptions) that feature this symbol meeting its demise under the pressure of stark reality. Some falls are self-induced in these stories, some unjustly inflicted, some dramatic, and some just quietly devastating (similar to the experience of James Tyrone Sr. in Long Day’s Journey into Night or of Esther from The Bell Jar), but all have one thing in common – their irrefutable tragedy, and its unfortunate continuation to the present day.

I. The Grapes of Wrath

Many Steinbeck’s classics centre on the Fall of the American Dream, but since The Grapes of Wrath deals with the immediate horrifying experience of the Great Depression, it tops the list. This is a resolute novel about the unattainability of the American Dream, as the story focuses on one family fleeing destitution of the mid-west only to arrive at California’s very own “human slaughterhouse”. “How can you frighten a man whose hunger is not only in his own cramped stomach but in the wretched bellies of his children? You can’t scare him – he has known a fear beyond every other.”

Continue reading “10 Classic Stories About the Fall of the American Dream”Jacek Malczewski: Polish Symbolism

Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929) was a Polish symbolist painter who was part of the patriotic Young Poland movement, and whose work incorporated such motives as Polish history, folk-tales, mythology and Romanticism. Below are three of his artworks considered among some of his most awe-inspiring.

Melancholia [1890/94]

The artist’s best-known painting Melancholia is a work of feverish, staggering genius, which elicits an emotional, instinctual response, even if we are not sure which one. In this painting, whose precise meaning is open to various interpretations, we see “a hallucinatory whirlpool” of different emotions, memories, figures and impressions, with the figure to the right being presumably Melancholia herself, dressed in black. To the left, images of peasants and freedom fighters probably tell us of the unsuccessful Polish uprising of 1863, which resulted in apathy and gloom, again conveyed by Melancholia. The revolutionary colours of white, red and blue are emphasised in the work to underscore the struggle, while the black is also noticeable to hint to us of beauty, freedom marred.

Continue reading “Jacek Malczewski: Polish Symbolism”Review: The Liar by Martin A. Hansen

The Liar [1950] – ★★★★1/2

You say the most important thing as indirectly as possible in your story, and that is how you truly capture the attention and interest of your reader. In this classic novel by Danish author Martin A. Hansen (1909-1955), our narrator is schoolmaster Johannes Vig (Lye) living on one very small Danish island of Sandø – “a molehill in the sea”, and we all become “Nathanael”, an imaginary addressee of the schoolmaster’s sporadic diary-entries. While teasing and taunting his reader, Johannes details the natural beauty of the island and comments on its most illustrious inhabitants and their relationships. Local beauty Annemari wants to break off from her long-term beau Olaf, who is now away from the island. Olaf has been involved in a tragic boat incident some years previously, where one man died, and is apparently not the same anymore. Meanwhile one engineer Harry takes Olaf’s place in Annemari’s life, but the situation appears complex as Olaf’s return is imminent. As the novel so insidiously progresses, the question becomes: what is the place or role of our narrator, mysterious Johannes Vig, in all these happenings? Is his narrative reliable?, and if not, can we differentiate truth from fiction? While evoking the best of the epistolary literary tradition, notably George Bernanos’s The Diary of a Country Priest and Hjalmar Soderberg’s Doctor Glas, Hansen penned an existential novel about the gradual finding of meaning in the fleetness of life, and coming to terms with the passage of time in a remote place where time has stood still.

Continue reading “Review: The Liar by Martin A. Hansen”Review: Antidote to Venom by Freeman Wills Crofts

Antidote to Venom [1938] – ★★★★

“…of the Good in you I can speak, but not of the Evil. For what is Evil but not Good tortured by its own hunger and thirst? When Good is hungry, it seeks food, even in dark caves, and when it thirsts, it drinks even of dead waters” (The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran).

There are few murder-mysteries out there that have truly unique settings, and since this Golden Age detective mystery is set in a zoo, it certainly appeals just on the basis of its intriguing set-up. Irish author Freeman Wills Crofts (1879-1957)’s story is about Birmington Zoo Director George Surridge, whose life starts to slowly unravel right under his nose: he and his wife grow increasingly indifferent towards each other, he has recently forced to fire one of his zoo guards for misconduct, and now he has to deal with the most astonishing mystery: the disappearance of a poisonous snake from his zoo. That’s not all: following the snake’s disappearance, a man is found dead – presumably, from that snake’s bite. But, nothing is as it seems. Inspector Joseph French starts investigating and comes up with the most ingenious solution that would explain a whole sequence of odd events in George Surridge’s life. Antidote to Venom is one thrilling mystery read from one of the most esteemed Golden Age crime authors.

Continue reading “Review: Antidote to Venom by Freeman Wills Crofts”Hiroshige: Favourite Woodblock Prints

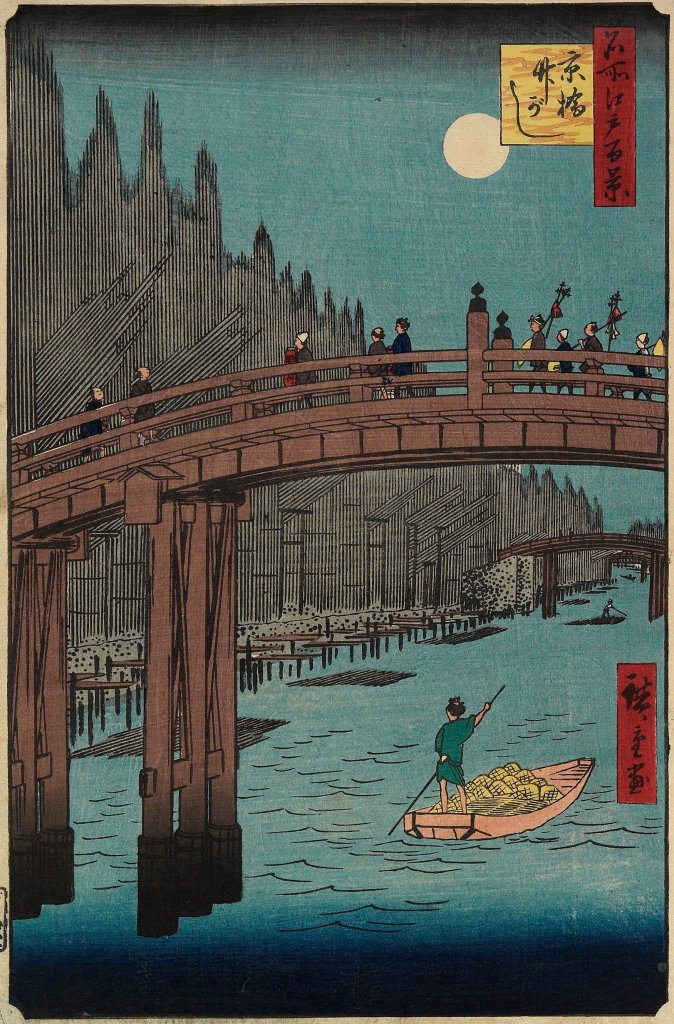

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo [1856-1858] is a popular, highly influential series of ukiyo-e prints of Edo (now Tokyo)’s environs produced by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). They offer views of Edo’s landscapes, temples, bridges, tea-houses, busy streets and people, often during seasonal festivities. They showcased unique for that time perspectives and offered unexpected insights, such as the interplay between the concrete and the abstract, the eternal and the mundane. The prints are not only masterworks, but also now a vivid throwback to Japan’s historic past with its long-gone traditions. Below are 15 of my favourite prints from this magnificent collection.

Bamboo Quay by Kyōbashi Bridge is one of Hiroshige’s nocturnal masterpieces in One Hundred Famous Views of Edo that shows the Kyōbashi river and its bridge being traversed by pilgrims. In the background, one can see drying bamboo rods of the bamboo quay. The painting probably influenced James McNeill Whistler in his artwork Nocturne in Blue & Gold: Old Battersea Bridge.

Continue reading “Hiroshige: Favourite Woodblock Prints”10 Women Authors From Latin America To Read

Happy International Women’s Day! Today, 8th of March, the world celebrates women, as well as their contributions, so I thought I would focus on women authors, highlighting the achievements of women authors from Latin America in particular. The list below presents 10 female authors (in no particular order) from Latin America worth reading.

I. Maria Luisa Bombal

María Luisa Bombal (1910-1980) was born in Chile, and gained prominence in her late twenties with books The House of Mist (La última niebla) and The Shrouded Woman (La amortajada). She also later published collections of short stories. Much of her work is focused on surrealist and feminist themes, as well as emotions and longing. I consider Bombal one of the most underappreciated female authors. She was once championed by Jorge Luis Borges, and some claim her book The House of Mist influenced Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (see also my review of her short story The Tree).

II. Clarice Lispector

“No it is not easy to write. It is as hard as breaking rocks. Sparks and splinters fly like shattered steel.” (Clarice Lispector)

Clarice Lispector (1920-1977) is definitely one of my favourite authors of all time. She was a writer from Brazil (born in Ukraine) with a penetrating writing style, and the ability to unravel the hidden and capture the unsaid. The Hour of the Star, Near to the Wild Heart and A Breath of Life are books of incredible originality, insight and nuance.

Continue reading “10 Women Authors From Latin America To Read”Ogura Ryūson: View of Yushima

[1880-1890] by Ogura Ryūson

This is painting Scene at Yushima by 19th century Japanese artist Ogura Ryūson. I do not know exactly why, but I fell in love with it the moment I saw it. There is something eerie and mysterious about it, and this feeling has probably something to do with Ogura’s effective shadowing, and the fact that the two male figures standing on an elevation are presented with their backs to us, facing the Moon.

Continue reading “Ogura Ryūson: View of Yushima”10 Best Short Stories I Read in 2023

Last year was a great year of reading short stories for me, and below are ten best short stories I read in 2023. I have to confess that I never used to read short stories, preferring lengthy novels and huge tomes of “substance” over short stories, but all this changed a couple of years ago when I discovered some great gems in this genre and my enthusiasm for short fiction has since only deepened. In 2023, I was particularly impressed by stories of James Baldwin, Anton Chekhov and Edith Wharton.

I. Sonny’s Blues [1957] by James Baldwin – ★★★★★

Baldwin’s Go Tell It On The Mountain was one of the last year’s novel highlights for me, but I also found this story by the author equally compelling. It tells of two brothers: our unnamed narrator, a conservative teacher, and his younger brother – free-spirited musician Sonny. The setting is the 1950s Harlem, and the unnamed narrator has just discovered that Sonny was arrested on drug charges. It is incredible how much power, emotion and thought Baldwin could compress into one single short story. Sonny’s Blues is about taking a nostalgic look at one’s life choices, dealing with loss, regret and the inescapability of one’s home environment, and copying with life dreams slipping away daily. It is also about the healing, transcendental power of music. Sonny’s Blues is not only the best short story I read in 2023, but one of the best I have ever read.

II. The House with the Mezzanine [1896] by Anton Chekhov – ★★★★★

This evocative, immersive story tells of a travelling landscape painter who, while staying at a friend’s house, gets acquainted with two sisters living in a neighbouring estate (the house with the mezzanine). One sister, strict and practical Lydia, works as a teacher and is engaged in her community’s political affairs, while the younger one, Zhenya, spends her time reading and day-dreaming. Our artist’s disagreement with Lydia’s world-view has long-term consequences when he realises that he has fallen in love with Zhenya. There are many themes that can be glimpsed in Chekhov’s delicate story, and one of them is spiritual, lofty ambitions, views and dreams clashing with daily realities and practicalities.

Continue reading “10 Best Short Stories I Read in 2023”Shōtei Takahashi: Night & Winter Scenery

From the end of the last year I have been actively into Ukiyo-e (a genre of Japanese panting), and would like to share some of my recent discoveries. Shōtei (Hiroaki) Takahashi (1871-1945) is considered to be one of the most prominent artists of the Shin-hanga (new prints) movement, which flourished in the early 20th century Japan and aimed to revitalise the traditional 17-19th century ukiyo-e art. Shōtei was raised in an adoptive family and was once an apprentice to his uncle, Matsumoto Fuko, who taught him Japanese-style painting. As a young man, he also worked for the Imperial Household Department of Foreign Affairs, and later for the Okura Shoten and Maeba Shoten publishing, as well as for the well-known Shin-hanga publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe, where he produced original designs. Below are some of his paintings showcasing the mysteries and wonders of the night, and winter season.

Review: Dandelions by Yasunari Kawabata

Dandelions [1964/2017] – ★★★★

“Dandelions cover the banks of Ikuta River. They are an expression of the town’s character – Ikuta is like springtime, when the dandelions bloom. Three hundred and ninety four of its thirty five thousand residents are over eighty years old…Only one thing seems out of place in this town: the madhouse” [Kawabata/Emmerich, Penguin Classics, 1964/72/2019: 3].

These lines begin Yasunari Kawabata’s novel which is about a young woman, Ineko Kizaki, who suffers from a strange, rare illness called somagnosia (fictitious) – the inability to see the body of another person. Ineko is in the Ikuta mental institution, and much of the novel is the conversation that Ineko’s mother and Ineko’s lover Kuno have on the way from the clinic after visiting Ineko. They both try to decipher the strange illness plaguing their loved one, but even the best Japanese doctors cannot help them, and the only conclusion reached is that maybe Ineko’s illness may somehow be connected with her seeing a traumatic event involving her father when she was young. Kawabata’s last book is gentle and restrained, but hides penetrating insights into the matters of the heart and mind for a reader willing to read between the lines.

Continue reading “Review: Dandelions by Yasunari Kawabata “7 Best Books I Read in 2023

I would like to wish all my followers a very Happy New Year! ✨ – let the year 2024 bring only joy, happiness and the fulfilment of all your wishes! Below is my list of 7 best books I read in 2023 (the best books I tend to read happen to be classics, and I am excluding non-fiction, graphic novels and short story collections).

I. My Ántonia [1918]

by Willa Cather – ★★★★★

This touching coming-of-age story by Willa Cather (Death Comes for the Archbishop, A Lost Lady) centres on Jim Burden’s friendship with one immigrant girl, free-spirited Ántonia Shimerda in Nebraska. Cather’s elegant prose simply enchants, and Jim’s distinctive voice is unforgettable, with each chapter brimming with soulfulness as it tells of immigrants’ hardships and sacrifices made through the years. It is a deeply nostalgic look at a life passed, as well as a sweeping expose of rural life in the late 19th and early 20th century America.

II. Go Tell It On The Mountain [1953]

by James Baldwin – ★★★★★

James Baldwin’s debut is a staggering book that focuses largely on John Grimes, step-son of the minister at the Pentecostal church in Harlem. John tries to make sense of his upbringing, environment and above all – all the expectations placed on him by others. This is a multi-dimensional and at times multi-perspective novel which also reveals issues of sexuality, racism and attempts at fitting in while remaining true to oneself. Baldwin’s prose cuts like a knife and yet remains touchingly lyrical throughout as the story recounts the accumulated heartbreak.

Continue reading “7 Best Books I Read in 2023”10 Novels By Contemporary Authors To Read If You Like Dickens

The novels of Charles Dickens are characterised by gripping plots, complex characters, and wondrous descriptions. But, what are some of the contemporary authors who also tried approaching their books in a Dickensian mode? Below are ten great books by contemporary authors who were either directly inspired by Dickens, imitating his plot structure or tone, or wrote their books having a truly Dickensian ambition.

The Luminaries [2013] by Eleanor Catton – In this highly ambitious, sophisticated, atmospheric and beautifully-written novel, Catton presents through an astrological chart mysterious events, including a disappearance and a possible murder, happening in Hokitika, New Zealand in the 19th century. Even Dickens himself never thought of doing something that eccentric with a book structure.

A Fine Balance [1995] by Rohinton Mistry – This book spins a powerful, heart-wrenching tale of four individuals whose lives intersect in the time of political and social upheaval in India in the 1970s. Recalling Dickens can feel almost an understatement to what Mistry really tried to achieve in this 600-page epic.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell [2004] by Susanna Clarke – “Dickens meets Harry Potter” is the best way to describe this ambitious alternative history fantasy that is about friendship between two very different magicians living in the 19th century England. Dickensian through and through, especially in its structure, characterisation, and language, it is probably the best fantasy novel I have ever read.

Continue reading “10 Novels By Contemporary Authors To Read If You Like Dickens”A Trip to London’s Anthropological Museum

I have recently visited the Horniman Museum & Gardens in Forest Hill, London. This is a museum established in 1901 and dedicated to anthropology and natural history. It is situated in a quiet, leafy area of London, and also boasts extensive gardens and an aquarium. Below are my highlights from this trip, with some excursions-snippets into topics and themes I found the most interesting.

- The World Gallery section of the museum is probably the most jaw-dropping, presenting various cultures through different elaborate displays of artefacts. I was drawn to learning about the cultures of people living in the Himalayan mountains, Africa, and North and South America. For example, it was interesting for me to find out more about the Wai-wai and Tuareg people. The Wai-wai are indigenous people of Guyana and northern Brazil. They nurture their children to become “real human beings” by sharing food, time and love. For them, “a real human is someone balanced, calm and beautiful, and knowledgeable about the world”.