“The painter should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself”(Caspar David Friedrich).

Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840) was a German Romantic painter, specialising mostly in landscape paintings. In time, his art had become hugely influential, making its mark on the art of others (Arnold Böcklin, Ivan Shishkin) and even on cinematography (Andrey Tarkovsky). Friedrich’s work has been described in many different terms: allegorical, melancholic, sublime, nature-focused, mystical and religious. What is clear, however, is the artist’s desire to convey to the viewer that unfathomable link between the external and the internal worlds that we all experience, and he would use landscape (“moodscape”), symbolism and other devices to convey his impenetrable “philosophy”. He was particularly interested in capturing the “stillness” of a moment/place and tying it to the deeper feelings of longing and wonder at nature, and life and its transience. Below I present five Friedrich’s paintings with some commentary.

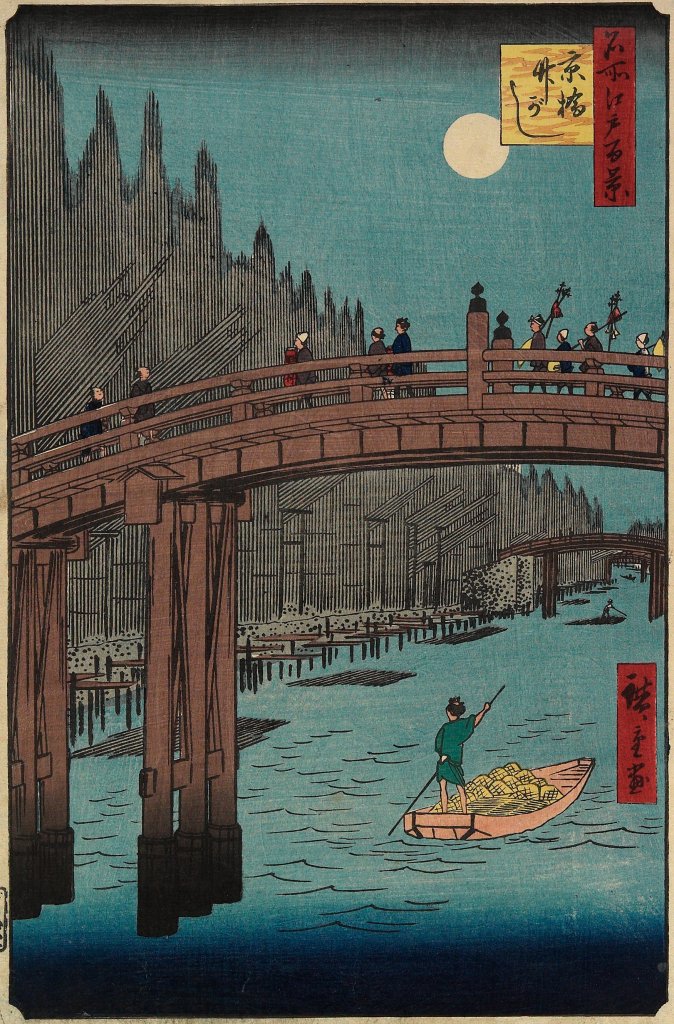

I. Chalk Cliffs on Rügen [c. 1818]

In this painting, the artist probably depicted himself, his wife Christiane Caroline Bommer and his brother Christian as this painting was completed just after Friedrich’s honeymoon to the island of Rügen, Germany. The serenity of the Stubbenkammer sea and cliffs contrasts with the activity of the three people in the foreground who find themselves dangerously close to the cliff’s edge.

As seen in other paintings by Friedrich, we can discern a fine symbolism and symmetry in this painting. The overhanging trees work as though a window-frame, presenting to us a lady wearing a red dress, which contrasts with the white cliffs and offsets the dark green and blue dresses of her companions. If the man to the right is completely immobile, standing arms crossed and reclining on what appears to be a dead tree, then the lady is leisurely pointing towards something in the abyss below and is in the sitting position, and the man in the middle (probably the artist himself) is on his hands and knees on the ground, looking in equal wonder at some scene unfolding below. Though the three people find themselves at a short distance from each other, the overall impression is still that of group unity and the three being comfortable around each other, perhaps feeling a little independent at that moment captured by the artist.

Continue reading “Delicate Symbolism & Transience: The Paintings of Caspar David Friedrich” →

I.

I.

I. A Woman Ghost Appeared From a Well (The Mansion of the Plates)

I. A Woman Ghost Appeared From a Well (The Mansion of the Plates)

I. Witches’ Sabbath [1798]

I. Witches’ Sabbath [1798]

I. Memory [1948]

I. Memory [1948]

It seems that every allegorical painting opens a door to deeper truth. The Calumny of Appelles was painted by Sandro Botticelli in 1494 from the description of a lost painting by Apelles, a Greek painter, who lived in the 4th century BC.

It seems that every allegorical painting opens a door to deeper truth. The Calumny of Appelles was painted by Sandro Botticelli in 1494 from the description of a lost painting by Apelles, a Greek painter, who lived in the 4th century BC.

These are the portraits painted by

These are the portraits painted by