The Films of Michael Powell and The Archers [1997] – ★★★1/2

A good, introductory book on The Archers’ craft, and how the times in which the directors worked impacted their cinematic masterworks.

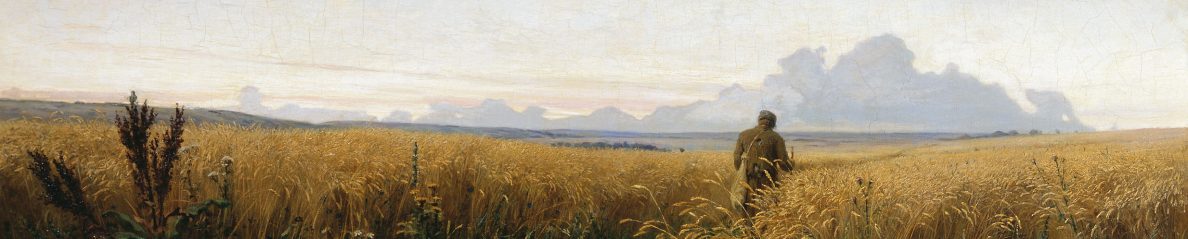

“In my films, images are everything” (Michael Powell).

The Red Shoes (1948), The Life & Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), Black Narcissus (1947), A Matter of Life & Death (1946) – these are some of the greatest films ever produced, but how did one unlikely duo of British film-makers, Michael Powell (1905-1990) and Emeric Pressburger (1902-1988), better known as The Archers, manage to achieve such level of cinematic mastery, while also working in a tricky political and economic situation, and more amazingly, without the support from Hollywood? In his bibliographical non-fiction, Scott Salwolke may not be unveiling all the keys to the mysteries of The Archers’ craft, but he certainly provides a fascinating historical background to many of their cinematic masterworks, focusing on the film-makers’ influencers and revealing how their films emerged to be so different from those of their contemporaries.

The book starts with Michael Powell’s biography, detailing his childhood, how he first came to work on films and what his first films were. It is the comparison between him and the great Alfred Hitchcock, which is intriguing here, for example, both were influenced by German expressionism that “infused both men’s work, and, because each had had their apprenticeship in the silent cinema, neither would trust the spoken world, preferring instead to rely on images to convey emotions and feelings” [Salwolke, Scarecrow Press, 1997: 8]. Both also used music in their films to heighten a range of emotions. Though both Powell and Hitchcock wanted to “make it big” in the cinema-world, it was Hitchcock who had eventually emigrated to Hollywood after producing a number of films in his native country, whereas Powell remained in Britain and faced all if its “1920s cinematic limitations”.

Then, there is a talk of Emeric Pressburger, and his early introduction to cinema. Born in Hungary, he first met Powell in 1939, and largely worked as a screenwriter, operating “behind the scenes”, whereas Powell directed actors and dealt with the press. Salwolke describes their partnership as “divine”: “Powell had discovered in Pressburger a writer whose sensibilities complemented his own”. Powell once wrote “I had always dreamt of this phenomenon: a screenwriter with the heart and mind of a novelist, who would be interested in the medium of films, ad who would have wonderful ideas, which I would turn into even more wonderful images, and who would only use dialogue to make a joke or clarify the plot” [Salwolke, Scarecrow Press, 1997: 59]. He certainly found that scriptwriter in Pressburger.

While it could be argued that Hitchcock’s films are more narratively persuasive and “wholesome” than those of The Archers, it should also not be forgotten that Hitchcock himself delved much into the narrative talent of others to produce his work, and many of his most celebrated films are based on, or were inspired by, books, including Vertigo (a crime novel by Boileau and Pierre Ayraud), Psycho (a horror book by Robert Bloch) and The Birds (a story by Daphne du Maurier). In contrast, Powell largely had only Pressburger, and their films’ “unexpected changes of register, from comic to serious, and their ironic detachment of form from content” could all be “attributable to Pressburger’s Hungarian background and [his] sophisticated experience scripting in Berlin and Paris. [From his previous work, Pressburger] learned the structural principles of ellipsis, allusion, rhyming and dramatic paradox” [Salwolke, Scarecrow Press, 1997: 104].

There are plenty of insights into some notable films in the book. Powell’s first colour film was The Thief of Bagdad (1940), and he also made a number of films that are now deemed lost. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted to ban Powell and Pressburger’s film The Life & Death of Colonel Blimp because it was perceived as “defeatist”, but, to be fair, the film just proves that the British can laugh at themselves, too, and find delight in showcasing their own eccentricities, understanding irony. Interestingly, Colonel Blimp wad made in the midst of the war, with threats of air raids, but its “ban” only translated into its commercial success. “It is a film light years ahead of its time, particularly in Britain when most films either seemed to be adaptations of literary masterpieces or attempted to mirror reality”, writes Scott Salwolke [1997: 94]. There is similar background information given regarding such films as The Red Shoes, The Small Black Room (1949), I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), Peeping Tom (1960) and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), the latter being described as “a baffling, tantalizing, but eminently noteworthy piece of perverse brilliance” [Salwolke, 1997: 193]. It was also Pressburger’s wife, Wendy, who first recommended him Rumer Godden’s novel Black Narcissus (1939), which then became one of The Archers’ best known films.

Often working with cinematographer Jack Cardiff, Powell and Pressburger used to carefully work out the look of their films before even production began, for example, through drawings and scale models. War definitely influenced the content of their films (some films began on governmental requests and the duo made some propaganda-like films (49th Parallel (1941), One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942))), but what distinguished their work was still that uncanny thematic fusion. Critics used to say that their films, even though very beautiful, were too unfocused, with unpersuasive storylines, but, in reply, it can be said that they simply possessed unusual rhythms and ambivalence. When formulaic story-lines with their clear-cut characters were deemed the only way to tell a story, the directors simply went for something different and unusual, with a touch of unexpected nuance or something macabre here and there, and much character and plot ambiguity, often making their audience find the story’s plot or its deeper meaning for themselves.

🎥 Powell and Pressburger showed the world that English cinema was able to compete on the world stage with American films, and the directors’ distinctive cinematic vision continues to be felt in today’s cinema (one of the people who champion their work today is none other than Martin Scorsese). Salwolke’s book may be dated and over-reliant on Powell’s own autobiography, but it does go into some depth regarding how certain films were made, and for those who are curious about The Archers, or have already seen and loved their films, the book would be a good resource and an enjoyable read.