Foucault’s Pendulum [1988/89] – ★★★★

“…the important thing is not the finding, it is the seeking, it is the devotion with which one spins the wheel of prayer and scripture, discovering the truth little by little” [Umberto Eco/William Weaver, Vintage Press: 1988/89: 33].

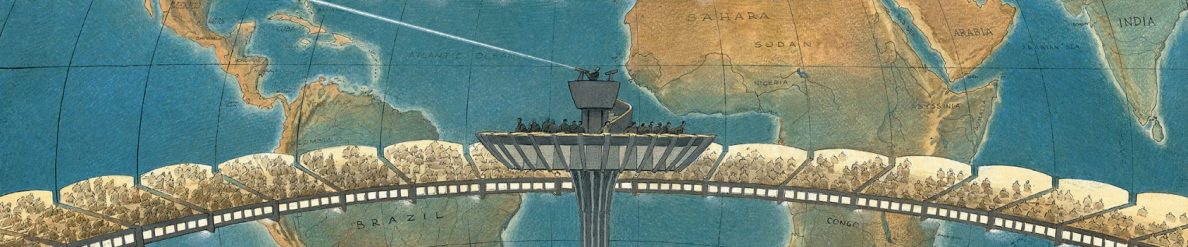

Through one dense, rich and enigmatic narrative, Umberto Eco tells the story of Casaubon (our narrator) and his friendship with two employees of publishing house Garamond Press – Belbo and Diotallevi. This trio of intellectuals, who are simply in love with all kinds of knowledge, historic mysteries and brainy puzzles, start their own intellectual “game” of drawing connections with seemingly unrelated things using one clever word-processing machine and a suggestion from one Colonel Ardenti which concerns the order of the Knights Templar and perhaps mysterious resemblances. Little do they know that their amassed knowledge will be too diverse and their power of belief – too strong for a game which started on a whim and so childishly. When certain deaths and disappearances occur as they the trio’s search for their ultimate and absolute truth continues, it may be already too late to seek the way out. But is Eco’s story even about that? Perhaps it is about something else too, and about something else, and, equally, about something else. From the intellectual hub of Milan to esoteric, mysterious corners of Brazil, Umberto Eco takes the reader on one uncanny literary journey and presents a narrative which informs, surprises and exhilarates, as it also confounds, exhausts and overwhelms.

The story is divided into sections titled after the ten Sefiroth of Kabbalah. We are first introduced to our narrator, Casaubon, who is hiding in the Musée des Arts et Métiers and narrates to us the events of past years. In previous years, he, then a PhD student working on the history of the Knights Templar, made good friends with Jacopo Belbo and his co-worker Diotallevi, both working at Garamond Press, and both being “walking encyclopaedias”, avid explorers of the secrets of the universe (they “would create hand-books for impossibilities, or invent upside-down worlds or bibliographical monstrosities”)[Eco/Weaver, 1988/89: 56]. Casaubon, initially a sceptic, soon gets himself entangled into Jacopo Belbo’s mind games and Garamond Press’s shady dealings.

The trio’s invention of the Plan, created after suggestions on the Knights Templar made by one mysterious Colonel Ardenti, signals their first step into intellectual abyss. And their Plan is as elusive as truth itself, “celebrat[ing] the nuptials of Tradition and the Electronic Machine [Eco/Weaver, 1988/89: 369]. Using one word-processing machine named Abulafia (“word processors could change the order of letters. A text, thus, might generate its opposite and result in obscure prophecies” [1988/1989: 33]), Belbo, Casaubon, Diotallevi starts feeding into it bits of knowledge from the most obscure and mysterious sources trying to make connections with seemingly unconnected trivia. Their obsession with their work grows daily as they try to penetrate the ultimate Truth by creating one obscure document and then by painstakingly reconstructing the said false text: “No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on one file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them” [Eco/Weaver, Vintage Press: 1988/89: 225]; “we mustn’t confine ourselves to the exterior, or to the surface reality of the dashboard; we must learn to see what only the Maker sees, what lies beneath”; “Any fact becomes important when it’s connected to another. The connection changes the perspective; it leads you to think that every detail has more than its literal meaning, that it tells us of a Secret” [Vintage Press, 1988/1989: 378].

The trio of friends also plunge deep into the history and mysteries of the Knights Templar, this order’s possible thirst for world domination and clues that this order might have left for their descendants, including rituals to complete to find the ultimate Secret. Speaking of rituals, our narrator Casaubon also travels to Brazil with his Brazilian girlfriend and there witnesses a number of esoteric rituals and attends extravagant séances. One of them is all about Brazil’s religion based on African beliefs Candomblé, while another – Umbanda is another practice that mixes African beliefs with Roman Catholicism and Indigenous American rituals. While all this is going on, love interests of the main protagonists appear and disappear, with Belbo being often sexually frustrated with regards to the novel’s femme fatale Lorenza Pellegrini, and Casaubon first having relationship with a Brazilian woman Amparo and then falling in love with Lia in Milan.

Writers are often given advice that if some beautifully-written paragraphs in their story do not fit into their story arc and generally feel out of place, they have to delete them no matter how attached those writers became to those paragraphs, i.e. they must learn to “kill their darlings”. Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum does not appear to be a book that followed this sound advice, and, seemingly, Eco did not attempt to “kill any of his darlings”, filling his book to the brim with the most erudite paragraphs on all kinds of mysterious rites and orders – and in all fairness – all soundly delivered. Diffusion/lack of focus is what ultimately characterises the book.

The conclusion is that Foucault’s Pendulum is highly erudite and labyrinth-like, riddled with historical curiosities, occult science and esoteric themes. However, the issue is that the book’s narrative thread is at times completely buried beneath the mammoth amount of diverse knowledge displayed by the three main characters. The mystery often finds itself at the complete mercy of the constant encyclopaedic digressions. Thus, if you do not mind in your literature the abundance of knowledge, obscure references to occult practices, almost constant philosophising and hard-to-decipher stories-within-stories, Foucault’s Pendulum may be a book for you.

What a great post, I had no idea what this book was about so thank you! I’m not sure if it’s for me but I’m certainly intrigued.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I tried reading this years ago but ended up DNF-ing it. I was so confused!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a wild book, I thought when I read it that maybe Eco was trying to confuse readers as thoroughly as his characters end up being. A difficult book to try and describe though!

LikeLike

Very true. The story itself seems like a product of the word-processing machine Abulafia!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful review, Diana! I’ve wanted to read this for a long time, but when I tried, it was too complex for me at that time. Need to give it a try again. Loved Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose. I’ve heard people say that Foucault’s Pendulum is even better. Thanks for sharing your thoughts 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! It is worth trying to read again, I think. And, I also love Eco’s The Name of the Rose and actually prefer it to this novel.

LikeLike

Glad you love Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose 😊 So tempted to reading it again. Hope to read Foucault’s Pendulum soon. Thanks for inspiring me 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read this ages ago and recognised this for what it seemed to be, a wicked commentary on conspiracy theorists and their thinking.

With the rise of the Internet the pernicious effects of such mindsets has worsened. In the 1980s it was all Holy Blood / Holy Grail and UFOs, and it has since taken via 9/11 to Trump apologists and anti-vaxxers.

I have to finish Middlemarch first though, before a reread if this Eco! Anyway, lovely review, it brought the flavour of the book back to me. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, Eco seems to be satirising conspiracy theories and the way these theorists can arrive at most unbelievable conclusions if they never question the value of certain “facts” and do not discriminate between one piece of trivia and another. I know it is all nonsense (probably!), but a romantic in me secretly thinks it must have been exciting to live in the times of the majority’s obsession with UFOs, trying to catch one in starry skies, thinking “what if” and following the news. I don’t know, there is something exciting in the whole thing and it brought communities together. And, thank you for reading and commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (1982) purported to reveal that the ‘sangreal’, supposedly meaning both the holy grail and royal blood, was a veiled reference to the direct bloodline of Jesus and Mary Magdalene manifested via a cryptic Priory of Sion, the Templars, even Nicholas Poussin, Claude Debussy and (inevitably) Leonardo da Vinci in a certain descendent Pierre Plantard, all bolstered by a concoction of cherry-picked facts, claims, fake documents, speculation and demonstrable errors.

I met one of the three authors of this farrago and a more conceited, self-important, strutting coxcomb I had yet to meet. It was all swallowed hook, line and sinker by a legion of avid fans, and still has its adherents today, four decades on. My friend Paul Smith has documented the whole cult thing at https://priory-of-sion.com/, and it’s hard not detect echoes of Eco’s title in this labyrinthine hoax.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, thanks for sharing! It sounds like one crazy mix of theories. I do have one book on Holy Grail on my TBR, actually – The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief by Richard Barber.

LikeLike

That’s a good collation of all that that’s known and surmised about the legend which I reviewed with another study back in the day: https://wp.me/s2oNj1-2grails

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is my favorite Eco! I feel that the diffusion is very much intentional, actually – this was written in a way to make and not make sense simultaneously, in a conversation with the reader, who may or may not pick up the challenge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I used to own this book and tried to read it a couple times but never got into it very far before giving up. About a year ago, I thought I’d give it another shot but couldn’t find the book. I figure that I gave it away at some point, trying to make room on my bookshelves. I loved The Name of the Rose even though that was also a challenging read. After seeing your review, I may give up on FP for good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sound like a curious yet playful book! Also seems like it has put off many readers from trying to read it with its maze of information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I loved The Name of the Rose, but I’ll pass on this one. I think it would bury me.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s a good one though. 😉(Fancy meeting you here) 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

My thought precisely! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

read it about 30 years ago. Maybe it’s time to read it again. (Doing that a lot lately…)

LikeLiked by 1 person