Medicine & Society in Later Medieval England [1995] – ★★★★

“Magic was…an integral component of medieval medicine”, tells us historian Carole Rawcliffe in this book on the state of medicine in later medieval England. And, not only magic. Religion, astrology and even art were all tied up in the practice of medicine in the Middle Ages, and this non-fiction sheds much light on how the medieval society in England viewed illness, and its diagnosis and treatment. What was the difference between the medieval professions of physician, surgeon, apothecary and barber? Why the state of medicine in England at that time lagged behind other European countries? What was the general attitude towards women connected to the practice of medicine? And, what methods were used when no proper methods of anaesthesia and sanitation were yet available to the medical personnel? Relying much on the contemporary accounts, Rawcliffe proves to be an expert guide on these questions and many more, and her book is a scholarly, but also highly readable, journey into England’s medieval past.

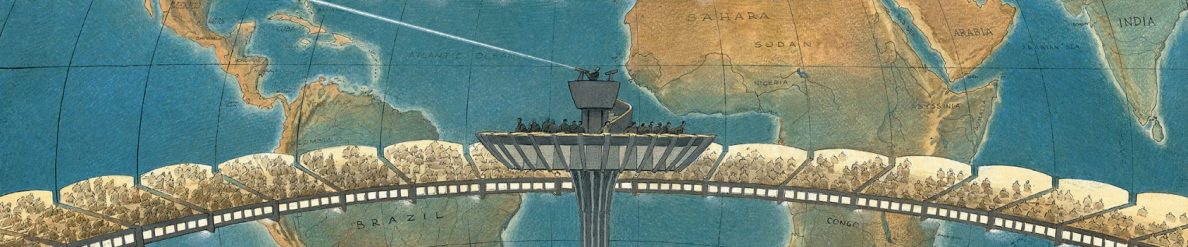

In the Middle Ages, death was omnipresent. Epidemics, famine, wars, infant mortality and injuries are all just the tip of the iceberg in the ocean of the causes of death in medieval times. The average life expectancy was 29 years from birth (Florence, the 1420s), and illness was viewed both as a gift from God, and as a sin and punishment to endure, depending on the moral standing of a patient. Medicine was governed by Galen and Hippocrates’s teachings, including by the theory of the four humours: choler, phlegm, black bile and blood, which corresponded to the four elements making up the universe (fire, water, earth and air), as it was believed that the human being is merely the mirror-image of the world, governed by the same principles. This idea was then applied to both the diagnosis of an illness and its treatment, which means that health was equated with humoural balance, and healing methods were often concerned with either retaining or defusing heat. The application of the theory cannot be understated as one example by Rawcliffe states “…two men suffering from identical wounds in the arm, inflicted at exactly the same time, should not necessarily be given similar treatment. On the contrary, the surgeon would have to adopt a radically different modus operandi if, say, one were sanguine (blood-governed) in temperament and the other proved to be melancholic (black bile-governed)…” (Rawcliffe, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1995: 56, quoting the Science of Cirurgie, compiled in 1296).

Uroscopy (the examination of urine) and, to a lesser extent, the examination of a pulse were both used to make a diagnosis. And, this could be coupled with the chart on the patient’s planetary influence and the consideration of their immediate environment. Blood-letting (phlebotomy) was common as treatment, but also performed on perfectly healthy individuals and regularly, as it was deemed prophylactic, cleansing the body and ridding it of excess humours. Rawcliffe’s chapters then focus on the physician, surgeon and apothecary professions, and much detail is provided on each of them. It may surprise the readers to discover that, back in the day, a physician was expected to be well-versed not only in logic, grammar and astrology, but also in rhetoric and music, and it is these, together with his medical knowledge and experience, that dictated his reputation. A physician in the Middle Ages also considered himself “above” performing any surgery, which was often left to surgeons or barbers, who often had only rudimentary knowledge of it. So, the prestige that we now attach to the profession of a surgeon had yet to come. However, England’s medieval medicine was not all guesswork, incantations and spiritual guidance, and the merit of the book is that the author points out the sceptics of certain treatments along the way. Wisdom did at times prevail over planetary fabulas, and some physicians recommended sensible things to their patients, including a moderate diet and balance in all things, criticising the popularity of blood-letting.

One chapter of this book is titled “Astrology & The Occult”, and Rawcliffe then devotes two whole chapters to the position of women vis-à-vis the medical establishment. She writes that women played an ambivalent role regarding their involvement in medical matters and caring for the sick, though, more often than not, they were victims of much prejudice and suspicion.

At times, Rawcliffe’s narrative gets bogged down in all the little details, such as the financial affairs of the medical profession, but the author often manages to “rescue” her paragraphs with many exciting and interesting examples. The book also leans on the academic side, but that also has its advantages, and one of them is that the reader will get only what they have opened this book for – a thought-provoking insight into medieval medicine, rather cringey pop culture references or the author’s irrelevant biographical details, as it is so often the case with more popular history non-fiction (see my list of 7 Fascinating History of Medicine Non-Fiction Books).

⚕️ Together with the Crusades and the Black Death, the medieval state and practice of medicine are the most fascinating topics connected to the Middle Ages. Intelligent, eye-opening and well-illustrated, Medicine & Society enlights on this topic thoroughly, emphasising the sheer gulf between medical theory and practice at that time, as well as the difficulty of reconciling the spiritual (e.g. religious teachings) with the physical (e.g. scientific observations).

Sounds really excellent, thanks for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

The author’s irrelevant biographical details often seem to pop up in journalism and non-fiction these days. I enjoyed this review thank you. I am particularly interested in how spiritual and even magical aspects of thinking influence our perception and knowledge of medicine – even today – so I’m definitely going to give this one a go.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I think authors only think that this information about them is interesting and “eases” us to some “heavier” material in the text, but it only annoys and exasperates actually, in my personal opinion. It also crops up in film reviews, like reviews open with: “My kid hates Mickey Mouse” or “My childhood was filled with Superman”. I see how this sentence may get us reading further, but really…Naturally, most people regard their lives as very interesting, and want to share it, but more often than not, I find this info quite needless. This does not apply to all non-fiction, of course, and it depends on how this bio is presented, but I also guess it is like telling someone of a dream one had. It may mean a lot to that person and is full of significance to them, but being on the receiving end of such a tale may not be as exciting as that dreamer thinks it is 🙂

And, yes, if you are interested in the influence of magical thinking on medicine, this is the book to read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do believe it will be just what I need. So thank you so much. Your blog is amazing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post! It offers an enthralling glimpse into mediaeval medicine, where magic, religion, astrology, and art were all linked. I love the examination of occupations, attitudes towards women, and the difficulties encountered in the absence of contemporary innovations. Carole Rawcliffe’s book is a serious yet enjoyable voyage into this fascinating subject. Thank you for providing this fascinating look at mediaeval medicine!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good, both the book and your great comment, thanks.

I remember also 3 interesting publications I consulted time ago related to this matter:

– BRABANT,H. Médecins, malades et maladies de la renaissance. Bruxelles, La

Renaissance du Livre, 1966.

– MOORE, R.I. “Heresy as Disease” en De Concept of Heresy in the Middle Ages,

Leuven-The Hague, 1976

– DELUMEAU,J. La peur en Occident.Paris, Fayard, 1978.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much, I will look into them. I also find French scholarship more or less unparalleled when it comes to this period.

LikeLike

This sounds absolutely fascinating. Whilst much of the mumbo jumbo may have moved on, I wonder how far medicine has really progressed (particularly for women). Lovely review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If my experience is anything to go by, I’d say quite a lot. For the emergency bilateral orchiectomy I had to undergo, I think I was the only man in the operating room – surgeons, anaesthetist, nurses were all women.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We need to get back to medieval medical treatment

LikeLike