Death Comes for the Archbishop [1927] – ★★★★

This novel, which spans from 1848 to 1888, focuses on Jean Marie Latour, a young Frenchman recently appointed as Vicar Apostolic in the state of New Mexico, a part of land which has only recently been annexed to the US. The Father becomes a new Bishop in the region and he came there with his loyal friend and compatriot Father Joseph Vaillant. The two priests face a whole array of problems in establishing a religious jurisdiction in the new area, from the region’s isolation and merciless climate to authority challenges on the part of Mexican priests. This historical novel can be called a “descriptive tour de force”, rather than a straightforward narrative story. It is more of an anthropological/historical travelogue, focusing on the nature of land and on the people living on it, rather than a linear story. However, this does not make this book a “lesser” novel. On the contrary, Cather leaves plenty of space in the book for colourful descriptions of exotic environs, paying attention to the particular themes, including the ardour of religious duty and the dilemmas of missionary work.

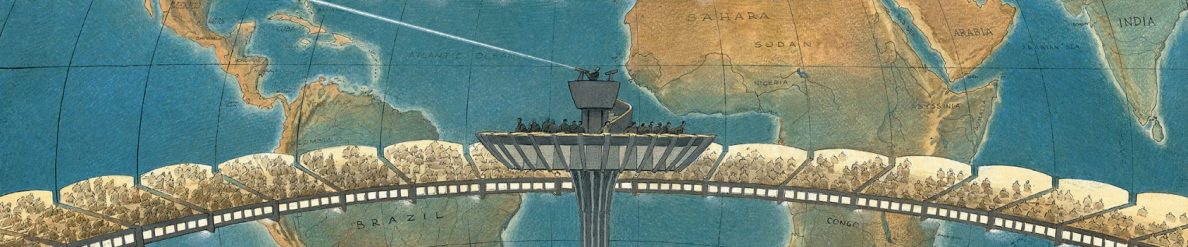

Willa Cather sets her novel in interesting times in a land “barely discovered” and in many aspects – still unknown (“in a dark continent”) [Cather, 1927: 21]. The land and the region take the central place in Cather’s story. We get to know such places in New Mexico as Santa Fe and Albuquerque (obviously), but also Pueblos Acoma and Taos, among others. We are permitted in this story to “savour” each of these places and their atmosphere: “as far as he could see, on every side, the landscape was heaped up into monotonous red sand-hills”…”they were so exactly like one another that he seemed to be wandering in some geometrical nightmare”…”[the] mesa plain had an appearance of great antiquity and of incompleteness; as if, with all the materials for world-making assembled, the Creator had desisted, gone away and left everything on the point of being brought together, on the eve of being arranged into mountain, plain, plateau. The country was still waiting to be made into a landscape” [Cather, 1927: 18, 95].

The author based her book on real historical events, drawing inspiration from the life of Jean-Baptiste Lamy [1814-1888]. The novel provides a curious insight into another life and place, and it is always fascinating to read about the establishment of a religious order in a completely foreign and unknown land, about the challenges that this feat presupposes: “that is a missionary life; to plant where another shall reap” [Cather, 1927: 39]. Such books as Shūsaku Endō’s Silence [1966] and Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible [1998] deal with this theme thoroughly. In the same vein, in Death Comes for the Archbishop, we simply follow two priests who go about their business, visiting villages under their religious jurisdiction. Along the way they meet various characters (some threatening and some very kind), and there are stories within stories. The encounters with Native American, Mexican, American and European characters are presented vividly alongside certain insights, such as on the mentality of Native Americans or on the nature of worship: [American Indians] seemed to have none of the European’s desire to “master” nature, arrange and re-create. They spent their ingenuity in the other direction, in accommodating themselves to the scene in which they found themselves” [Cather, 1927: 234].

Father Latour (Bishop) and Father Vaillant (Joseph) soon realise that in new and hot New Mexico their duties encompass not only priestly matters, but they also have to be part diplomats, part traders, part translators, part governors and even their own cooks – all by sheer necessity. The two men share great friendship, but as Father Latour grows more lonely and homesick as time passes, his colleague Father Vaillant, who can feel at home anywhere, feels invigorated by the challenges and want to help as many people as possible. Also, if Father Vaillant overlooks material possessions and prefers to live humbly, Father Latour has a deeper appreciation and craving for material things that will stand the test of time. So, he decides that a magnificent cathedral should be built in the area so that this building will be “a continuation of himself and his purpose, a physical body full of his aspirations after he had passed from the scene” [Cather, 1927: 175].

One negative aspect of the novel is that Willa Cather sometimes blatantly casts aside the golden rule of fiction “show, don’t tell”, but, to compensate for that, the slow-moving novel also has descriptions that never rush forward and this allows the story itself a space “to breathe”. There are also some generalisations and stereotypes presented, especially regarding native Mexicans as they are contrasted with “educated” Europeans, and Cather should have stuck to just one name for each of her main characters because both of them have three names each in the story and the author uses them interchangeably, causing confusion.

† This book with a rather “scary” title hides a gentle narrative that focuses on a particular place and its peculiarities – New Mexico in the mid-1800s. Death Comes for the Archbishop is a fine literary homage to the region’s beauty, mysteries and history.

One negative aspect of the novel is that Willa Cather sometimes blatantly casts aside the golden rule of fiction “show, don’t tell”, but, to compensate for that, the slow-moving novel also has descriptions that never rush forward and this allows the story itself a space “to breathe”. AS YOU STATE

I like the way you say this, Diana. It’s an interesting, provocative observation, well put and thought provoking.

I was thinking of the first chapter of Balzac’s “Pere Goriot.” There is a considerable amount of “telling,” interpolated commentary by Balzac, but it heightens reader interest rather than the converse.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! And very true about Pere Goriot’s first chapter. I love it and can re-read it endlessly. I think it all also shows that there are no hard and fast writing rules and it all depends…on many other things, on a book, chapter, aims, the style of writing – what will never work in many books may work perfectly in another.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Diana. Genius and “perfection” are not necessarily the same thing. May I remind your readers of my own post about “Père Goriot” at

https://rogersgleanings.com/2020/07/28/balzac-le-pere-goriot/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Diana — I read Cather’s “My Ántonia” quite a while ago. I thought to myself, I have got to get to know her better; I may have read another one of her works. I know I purchased some. Anyway, I was very impressed by “My Ántonia.” It is about an immigrant family — I think from Czechoslovakia. How Cather wrote with such a deliberately “plain” style — it seems very fitting for the West of the Great Plains, a sort of beauty in “monotony” and “barrenness” (not really). The very opposite, say, of a writer like Nabokov or John Barth, and so many others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for recommending My Antonia! Emma from Words And Peace below has also recommended to me this book and I will hopefully read it in very near future. That is very true what you say about the author’s writing style and that it a great thought that it corresponds to the land she describes. I also found her writing gentle, deeply descriptive, but also quite unassuming even (without certain “self-importance” that categorise other writers). Perhaps I feel this way because she likes to present a story through a prism of a locality and that also gives the feeling of certain “quietness” to her work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I … found her writing … quite unassuming … without [a] certain ‘self-importance’ that categorise[s] other writers” …. ”she … present[s] a story through a prism of a locality and that also gives the feeling of certain ‘quietness’ to her work.”

I admire the way you put things, Diana. Very subtle and penetrating; and (as I said) well put.

Yes, unpretentious, direct. The author does not “get between” the reader and the characters, narrative.

Yes, one feels such a sense of locality: the West.

Quiet. Unassuming. I felt this very strongly too — in Cather’s writing. Not strident. The opposite of bombastic, tendentious, or grandiose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this. I particularly enjoyed the quotes you have used about the red sand hills and the idea of the two priests struggling on having to inhabit a dozen roles. I have read Willa Cather’s ‘Song of the Lark’ which is based on the life of the Swedish Nightingale, Jenny Lind.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very interesting. I did not know this. Makes me want to read “Song of the Lark.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you enjoy it if you do. It’s one of my top 20 books on the planet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I have just put “Song of the Lark” on my TBR! I love books that focus on artists and their struggles. I don’t think I ever read fiction that centres on an aspiring opera singer, sounds totally fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s amazing. Let me know what you think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You make me want to re-read this one. It’s a good time of year for it, still winter in Ohio where I’m longing for the blue skies of New Mexico.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful review! My Ántonia is also beautifully written

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t resist mentioning (completely irrelevant) Harrison F. Wisebite in Anthony Powell’s Books Do Furnish A Room. Jenkins: “Harrison I liked in his way. He mixed a cocktail of his own invention called Death Comes for the Archbishop.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never read, but I guess the cocktail was a tequila-based one? 🙂

LikeLike

We are never told in the novel – but you’re right: it should be tequila. I’ll have a go at thinking up a good mix. I’m something of a master of the authentic literary cocktail ☺️ see https://robinsaikia.org/excerpts/death-in-venice-cocktail/

I envy you not having read A Dance to the Music of Time, of which Books DFAR is one of the 12-volume sequence. You have a treat in store.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have now put it very high on my TBR list, thanks a lot for this great recommendation!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read this post again today, Diana, mistakenly thinking it was a new post. It is very well done and written.

Regarding the experiences of missionaries in a strange land, it’s not the same thing, but the historian Francis Parkman is a great writer. I have read “The Jesuits in North America” (two volumes; I think that’s the correct title). An original and totally absorbing work. It is at times very depressing because of accounts of torture by the Indians. It is a classic work which seems to be largely forgotten. Parkman is worth reading for his style alone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“The Jesuits in North America” sounds great, thank you! I have just read the description and it really sound like an unjustly forgotten, important book.

LikeLiked by 1 person