My Name is Red [1998/2001] – ★★★★★

My Name is Red [1998/2001] – ★★★★★

A rich, tightly-woven literary tapestry whose secrets lie in elaborate details, red herrings and in the depth of the soul of its maker, celebrating the beauty, imagination and intelligence of ancient artworks and methods of painting.

“Why does man not see things? He is himself standing in the way: he conceals things.” “What are man’s truths ultimately? Merely his irrefutable errors“. (Friedrich Nietzsche)

In My Name is Red by Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk, the murder of one miniaturist – Elegant Effendi – was committed within the circle of miniaturists working for the Sultan in medieval Istanbul. At the same time, thirty-six year old Black returns to his hometown of Istanbul after the absence of twelve years to seek once again the hand of his beloved Shekure, an opportunity that was denied to him twelve years previously. Unwittingly, Black becomes entangled in the intrigues of miniaturists working under Enishte Effendi, Black’s uncle and Shekure’s father. Masterfully, Pamuk takes us deep within the art circle of medieval craftsmen who labour to produce a mysterious new book, a circle replete with professional jealousy, narcissism, hidden love and, above all, differences as to the proper way of painting and representing pictures under one strict religious canon. In this historical novel, Persian art-forms clash violently with rising Venetian art influences as Black starts to realise that, in order to find the murderer of Elegant Effendi, it is necessary to go deep into the worldviews and art opinions of each of the three suspected miniaturists – “Stork”, “Olive” and “Butterfly”, testing their loyalties and beliefs.

Firstly, My Name is Red is an intriguing murder-mystery that plays with the reader, challenging them to identify the murderer before they reach the end. There are some clues as to the identity of the murderer scattered about in the narrative as we read about secrets that harbour the four great miniaturists – “Stork”, “Olive”, “Butterfly” and murdered Elegant Effendi – while working for the Sultan through both Master Osman and Enishte Effendi. These two masters have different views about the rise in popularity of Venetian art-forms and their influence on their traditional methods of painting.

Who could have killed Elegant Effendi? Another jealous miniaturist? Or maybe a religious fanatic dissatisfied with the way the four miniaturists started working on a new book in secrecy? What is the nature of the new book commissioned by the Sultan? Was it really designed to depict images that go contrary to Islamic faith? Black soon finds himself tasked not only with winning Shekure and her father’s affection, but also finding the murderer as another murder is committed soon afterwards and Shekure feels torn between her allegiance to her brother-in-law (as matrimonial law dictates since her husband has not been declared legally dead) and her devotion to her father. Black realises that, to know the identity of the murderer, it is necessary to go to the earliest foundations of Persian art, its inspirations and consider the nature of its relationship with its western counterpart. Pictures start to speak volumes in the book as Black discovers how past artworks shaped the present miniaturists’ styles and it is here that the answer to the murder puzzle may lie.

“The beauty and mystery of this world only emerges through affection, attention, interest and compassion; if you want to live in that paradise where happy mares and stallions live, open your eyes wide and actually see this world by attending to its colours, details and irony” [Pamuk/Göknar, 1998/2001: 452].

Two previous books that I reviewed – Mohsin Hamid’s Moth Smoke [2000] and Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World [2019] can be compared to My Name is Red since the three most likely drew inspiration from a common source/literary tradition. “Coincidentally”, Shafak’s book 10 Minutes 38 Seconds begins the same way as Pamuk’s My Name is Red – one spirit of a dead person starts talking to us, explaining their curious position and seeking retribution. In My Name is Red, the spirit of dead Elegant Effendi, whose corpse was thrown into a well, starts to recall his life and we get to know his professional circle. Also, as in Mohsin Hamid’s Moth Smoke, My Name is Red presents its story from the multitude of viewpoints, each competing for our attention as we read on and each trying to convince us with its rightness. If in Moth Smoke, there were only three or four other perspectives, in My Name is Red there are perspectives of Black, Shekure, Esther, Enishte Effendi, Master Osman, the three remaining miniaturists, not to mention the perspectives of inanimate objects and animals. The book results in a psychologically-intense ride that presents curious (sometimes black humour) situations that are recounted from different points of view. It is as though Pamuk does not let us see the wood for the trees – as we read on, we are blinded or diverted by different subjective opinions which do not let us see the broader picture or “objective” truth. Paradoxically, we, as readers, are both omniscient as to what is going on and “blind” at the same time because, even though we are cognisant of what is going on in the minds of each of the narrators, we are not told the most important thing and get lost in numerous details of the narration.

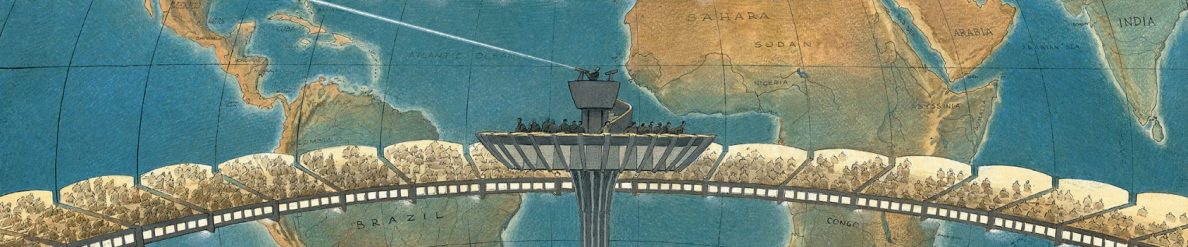

Secondly, My Name is Red is a deep reflection on the nature and the making of art – on its outside influences and development. Pamuk pits the Eastern tradition of art presentation (that puts emphasis on repetition and on the anonymity of artists) against the Western influence (including signatures and portraiture). Many characters in the novel lament the growing “westernisation” of their art, fearing what will be the final consequence regarding their religion and traditions. Something is being lost in their loyalty and devotion to Allah as art starts imitating life too closely (only Allah can be the source of all true creations) and certain unworthy personages take the central stage in paintings.

There are also fears of Ottoman art’s historic roots and old masters’ methods being forgotten and ignored through the vanity of certain miniaturists who want to leave their own signatures or new styles behind. Thus, amidst the murder-mystery, there are also fables told on painters’ styles being equated with mistakes, and on the admirable nature of blindness for artists as Black tries to make sense of this paradox of the trade of making pictures in a Muslim city, hoping it will lead him to the murderer: “the sincerity of the miniaturist….doesn’t emerge in moments of talent and perfection; on the contrary, it emerges through slips of the tongue, mistakes, fatigues and frustration” [Pamuk/Göknar, 1998/2001: 243]; “what exposes us is not the subject, which others have commissioned from us…but the hidden sensibilities we include in the painting as we render that subject” [Pamuk/Göknar, 1998/2001: 422]; “a great painter does not content himself by affecting us with his masterpieces; ultimately he succeeds in changing the landscape of our minds” [Pamuk/Göknar, 1998/2001: 258]. Pamuk lets us step within the beautiful paintings of the old masters of the Ottoman Empire and we walk through the armies and lovers gazing at each other from across the distances, enabling our imagination to fuse with the best paintings made in the Middle East.

There is a third aspect to My Name is Red. We get to know Shekure, the beautiful daughter of Enishte Effendi, quite well – her husband is presumed dead after he marched to war four years ago and she is left with her two young sons. The arrival of Black disrupts her brother-in-law Hasan’s courtship of her and we realise that Black has always been passionately in love with Shekure…or has he? Here, art creeps in once again and life starts imitating art. The subjective nature of love is linked to the subjective viewing of artworks, and Black and Shekure’s courtship is linked to one of the oldest Persian fables – Hüsrev and Shirin by Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi, as well as to the falling in love with the presentation of the image of one’s beloved first: “love…must be understood, not through the logic, but through its illogic” [1998/2001: 658]. The colour red subtly creeps in and repeats itself where we find ourselves closer to truth. Red stands for blood and violence, but also for passion as Black’s lust becomes uncontrollable even though his heart remains “pure” like that of a child: “for if a lover’s face survives emblazoned on your heart, the world is still your home” [1998/2001: 49]. Satan and Death both have their say in this book too – “what we essentially want is to draw something unknown to us in all its shadowiness, not something we know in all its illumination” [1998/2001: 202], and, by the end, the book becomes one unforgettable adventure into the mysteries of art, life, love and death.

🕌 The conclusion is that My Name is Red, translated from the Turkish by Erdağ Göknar, is an evocative, richly-layered and vivid murder-mystery with one unusual structure that immerses us into the mysteries of Ottoman paintings and in the atmosphere of medieval Istanbul. It is a true page-turner steeped in the history of the Ottoman art where fables and reality, as well as life and art, inexplicably merge to produce a one-of-a-kind story.

Great review, Diana! I always enjoy your layered analyses of what you read. This sounds like it’ll be right up my alley – a murder mystery AND a book about art in a medieval setting? I can’t resist that combination. Hopefully I can obtain a copy this month. (Also, this is completely unrelated and trivial but my curiosity has reached a breaking point and I have to ask – what’s the citation style you’re using? I’ve never encountered it before, but it looks like a parsimonious way to reference books.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I hope you enjoy this book! Citation style? I guess it is a variation on in-text Cambridge University Press.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review, adding this on my TBR.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This book looks incredibly interesting. And I love unique settings for murder mysteries, but the idea of a lush setting and the perspective of the victim himself is fascinating! I really enjoyed reading this review and will definitely be putting the book on my TBR.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot, and I hope you enjoy the book. It is very good, but quite unusual too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve understood this book so well. I tried to read it twice and failed both times, about two-thirds of the way through. Third time lucky as they say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you manage to read it third time. It is not an easy read but I thought it did tie things up nicely at the end.

LikeLike

Lovely review, Diana! You’ve reminded me I need to get ahold of this book 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating and in-depth review. I have been meaning to read Pamuk, and this helps to persaud me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love your reviews Diana…I have been eyeing this book for a long time and definitely now I will get it. I have to admit I skim-read this so that I didn’t find out too much of the plot. The setting, characters, Pulitzer and your five stars won me over completely! Thank you 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you like the book! I hardly put any plot and especially not spoilers in my reviews – but just try to talk about general themes. Somehow, in worrying times such as these, I reach not for comfort books, but the opposite – it seems, hmm.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I know what you mean…I feel the same too. Having books that are explainers or give some kind of clarity and address the situation going on, this can be such a comfort too. The book Black Swan by Nicholas Taleb is a good one for this, I don’t know if you have read that one, but it’s about the unforeseen scenarios like the one we are in right now. It is very difficult to read but also very comforting in a way, if you know what I mean.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreeing with everyone else, a great review. My Name is Red was my first Pamuk book, though it was Maureen Freely’s translation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I didn’t even know of that other translation, and it is certainly a great book to begin with this author.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad to read your review. I read Pamuk’s Snow many years ago and was extremely impressed with the prose but found the story difficult to get through. Last year we hosted an exchange student from Istanbul and she encouraged me to give him another try. However, she had no recommendations. Now I’ll add My Name is Red to my TBR list. Thanks much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading! I hope you like My Name is Red. I think that there is a little bit of everything there for every kind of reader – those who love history, those who love romance, those who love paintings, those who love murder mysteries, etc., and, of course, it is all rendered in Pamuk’s beautiful language (even if it is in translation). It is probably his best book. Since you love his prose, I can also suggest Pamuk’s The Black Book (if you have not read it already) – that one is very meditative, eerie and thought-provoking (it has something very special inside), even if the plot itself is a bit underwhelming.

LikeLike