The Blazing World [2014] – ★★★★1/2

The Blazing World [2014] – ★★★★1/2

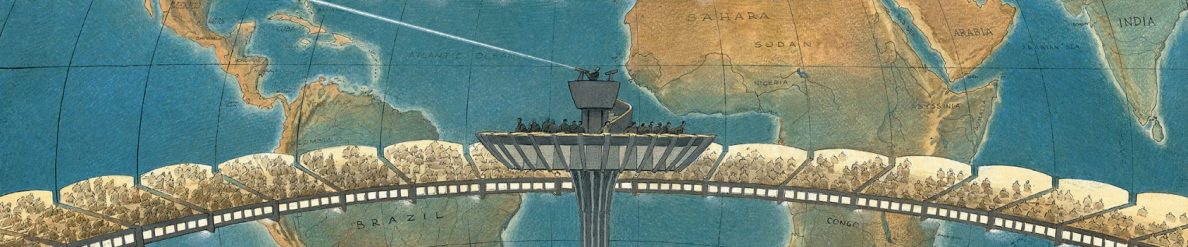

This longlisted for a Man Booker Prize book traces the story of Harriet Burden, a small artist and once the wife of an eminent art dealer Felix Lord. Through the statements from Burden’s family, close friends and acquaintances, we get to know the story behind Burden’s decades-long experiment to hide behind three male identities in the production of her art. Burden chose to create art and pass it as works by someone else, thereby, exposing the anti-female bias in the art world, but also the subconscious perception that male artists are much more brilliant than their female counterparts. The Blazing World is bursting with creativity, intelligence and originality. It touches on many philosophical and psychological issues, while also debating the nature of art, the process of its creation and human perception. At the heart of the story is one misunderstood individual whose depth and intellectuality may just signal her doom. This unusual book invites us, readers, to be archivists, observers, art critics, judges and psychologists, but above all, it invites us to look at the situation as human beings, trying to understand the feelings and thoughts of another.

In this story, Harriet Burden is a wife of the late Felix Lord and an artist who created artworks in the 1970/80s New York City that never had major success. Burden also claims that she created very successful artworks publicly known to be created by three male individuals: Tish (1998), Eldridge (2002) and Rune (2003). Burden says that she used these people as her “fronts” in her own experiment titled Maskings that is designed to expose the anti-female bias among art audiences and critics. And, in spite of all her eccentricity, it is difficult not to side with Burden because her voice in the narrative is the boldest and most confident as she states that “all intellectual and artistic endeavours, even jokes, ironies and parodies, fare better in the mind of the crowd when the crowd knows that somewhere behind the great work or the great spoof it can locate a cock and a pair of balls”.

Burden as a person is very interesting, and her situation and experiment are fascinating. The picture that emerges is of her as a lonely, shy and intelligent woman who thought that her own sex impeded her from reaching societal success and recognition. We learn that she is a very introspective person who tries to understand herself and the causes of things – “why do I feel there is a secret I carry in my body like an embryo, speechless and unformed, beyond knowing?” [Hustvedt, 2014: 64], she inquires, as well as asks “why am I a foreigner? Why have I always been outside, pushed out, never one of them? What it is? Why am I always peering in through the window?” Indeed, Harriet may be too clever, too deep, too reserved, too strong, too female, too intellectually-intimidating and too emotionally-sensitive, to be recognised, accepted, and fully acknowledged and praised for who she really is. “My mother was interested in everything, and she seemed to have read everything”, says her daughter [2014: 23]. The society does not seem to want to admit that Harriet or Harry (as some call her) does not want to be a beautiful and sublime Penelope who waits for her hero, but wants to be that clever and brave hero herself.

This misunderstood and undervalued artist who suffers from intellectual loneliness also has bold statements to make about art and human perception – “Awkward brilliance in a boy is more easily categorised, and it conveys no sexual threat” and “I doubt anyone can actually separate talent from reputation, when it comes down to it” [Hustvedt, 2014: 53/141]. Harriet is disillusioned with society and the art world, and craves connection and understanding in a loud and biased world that is too lazy to look beyond appearances. In fact, Harriet’s experiment Maskings is there “to uncover the complex workings of human perception and how unconscious ideas about gender, race and celebrity influence a viewer’s understanding of a given work of art” – “art lives in its perception only” [Hustvedt, 2014: 234]. Thus, there are many musings in this book on the nature of human perception and consciousness, since most of the time we truly only see what we expect to see and people are blinded by what they think they see [2014: 261/158]. There is also a hint in the novel that others’ impressions of one create that reality for him or her, and there is often a gulf between how society views us, and how we view ourselves and what we are truly capable of.

Unlike some others, I will never say that The Blazing World is a puzzle or a mystery. This is because, even thought we hear two sides to this story; there are unreliable narrators; and there are hints that Burden might have suffered from mental illness, we, as readers, still side with Harriet Burden. It is true that Harriet is a very eccentric woman who still grieves for her husband and becomes confused about her identity, as well as obsessed with revenge and her experiment, but her actions are still sympathetic and her situation – understandable.

The Brazing World may be too brainy, too pedantic and too repetitive, but its over-analytical, self-indulgent and pretentious nature is perhaps precisely the point of the book because the story is about privileged people’s troubles and the art scene permeated with abstract ideas, vanity and egocentrism. However, among all the intellectualisation and over-dramatisation, there is little emotion in this novel and different statements from people in the novel do put a barrier between the reader and the story. Also, when true emotion does come in the novel’s second half, it is something too little coming too late.

The Blazing World is clever, dense and sharp. It is a sophisticated work with an unusual structure which can only be compared to some object of modern art itself that purposely means to frustrate and confuse, but also to surprise and enlighten; like art itself, the book holds some deeper meaning for the reader, even if it is presented in an experimental and chaotic fashion.

Great review! I’ve not yet read anything from this author but have been wanting to- the modern art aspect to this one makes it sound like yet another great choice! I must pick up some Hustvedt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I hope you like this one if you get a chance to read it. I have heard that her novel “What I Loved” is even better, so I am looking forward to reading that one as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I hope What I Loved impresses you as well!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This ones been on my read list for ages. Thanks for this insightful review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting take on the novel. Hustvedt has always been a brainy writer and her works consistently appealed to a certain kind of readers. Although she hasn’t written a single mediocre novel, I think her early novels are the most accomplished ones. Especially the first three: The Blindfold, The Enchantment of Lily Dahl, and What I Loved. Being an expert on neuropsychology, she often draws on the latest researches in neuroscience and neurophenomenolgy in her writing and almost all her novels and nonfiction works explore the intricacies of the human mind, reception of art and reality, and how materiality informs consciousness.

On another note, I have always felt that Hustvedt is a better novelist and more sophisticated thinker than her husband, Paul Auster, although he enjoys a greater mainstream success.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, What I Loved is definitely very high on my TBR list, and I definitely get her interest in neuroscience from The Blazing World. I may agree with you that Hustvedt is a better writer, though I have not read Paul Auster and have only heard of his The New York Trilogy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure you’re going to like the rest of Hustvedt’s novels.

Auster’s The New York Trilogy is great; the only other book in his oeuvre that could be called great is his memoir The Invention of Solitude, an extraordinary book. None of his other works reach that level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot for these recommendations! I will have them in mind. I mean because it seems that Auster is preoccupied with existentialism, chance and the absurd, he should be a great read for me because I am very interested in all these themes too.

LikeLike

Actually now that I think about it, it is rather interesting that her husband enjoys a greater mainstream success, because it echoes The Blazing World, even though it is not any semi-autobiography – (or is it in a nutshell?) This novel is all about the wife creating art in the shadow of her husband and about the majority of people out there not appreciating fully the woman’s “intellectuality”, which means women undersell their philosophical work.

LikeLike

Very detailed and subtle review. I think in these days, we the privileged are in danger of disappearing down intellectual rabbit holes. Or possibly going around in circles, detached from life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is exactly the theme here – intellectual isolation and loneliness, and the construction of some ivory tower since the character feels there are few if any people there who can understand or connect with her. It is gaining all this knowledge and developing talent and then being disappointed with the society’s response.

LikeLike

I have seen this book and toss up whether or not to get it, your review has pushed me over the edge towards purchasing it. Sounds fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person